Lorsque George Leigh Mallory publie The Mountaineer as Artist en 1914, l’alpinisme est encore fortement structuré par des récits de conquête, d’héroïsme et de performance, ancrés dans une vision masculine, impériale et positiviste de la montagne. On célèbre les sommets, les premières, les records. On parle en termes d’objectifs atteints, de lignes vaincues, de cartographie achevée. Dans ce contexte, l’intervention de Mallory fait figure d’exception discrète, mais décisive.

Son texte, court mais dense, ne propose ni récit d’ascension ni analyse technique. Il avance une idée rare : que le grimpeur puisse être considéré comme un artiste. Non pas au sens figuré d’un « virtuose » ou d’un « génie », mais dans une acception beaucoup plus profonde : celle d’un être engagé dans une relation esthétique au monde, attentif à la forme de son geste, à la ligne qu’il dessine, à la qualité de son interaction avec le relief. L’ascension cesse alors d’être une performance à quantifier pour devenir un acte de composition éphémère, fait de justesse, de rythme, de style.

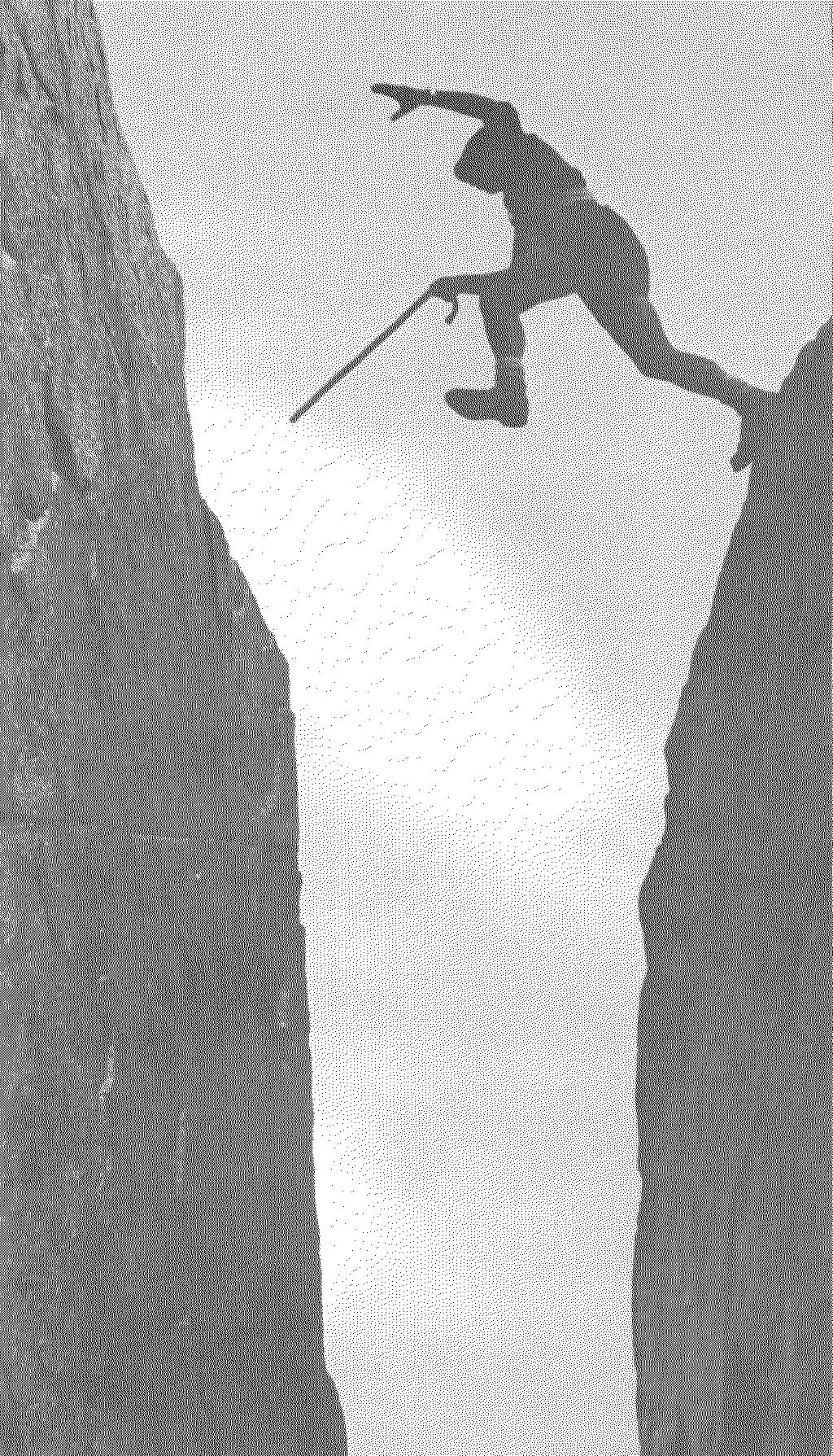

Ce changement de perspective implique une reformulation du rapport à la montagne. Le grimpeur-artiste ne cherche pas la victoire sur un sommet, mais une ligne « belle à tracer ». Il ne vise pas l’exploit, mais la cohérence entre le mouvement et le milieu. La paroi n’est plus un obstacle à franchir, mais un partenaire de dialogue, une surface de lecture, de contact, d’ajustement. Cette approche, profondément sensible, anticipe des notions que l’on retrouve aujourd’hui dans les réflexions sur l’éthique de la grimpe, l’attention au style, ou encore l’expérience esthétique des pratiques corporelles situées.

L’écriture de Mallory n’est pas théorique, mais elle mobilise un vocabulaire inhabituel dans le champ alpin : il y est question d’élégance, de ligne, de beauté - autant de termes qui ouvrent une autre lecture de la pratique. Ce n’est pas un manifeste, mais une inflexion. Une manière de faire entendre qu’il existe un autre rapport possible à la verticalité, où l’exigence technique se double d’un engagement esthétique et sensoriel. Une escalade non pas pour la gloire, mais pour la forme - au sens fort du mot : la forme comme manière de faire monde, de tracer du sens dans l’espace.

L’intérêt contemporain de ce texte tient aussi à son caractère ouvert. Mallory ne cherche pas à imposer une définition, mais à rendre perceptible une alternative. Dans un monde qui valorise de plus en plus la vitesse, la standardisation des méthodes, et l’optimisation des mouvements, The Mountaineer as Artist agit comme un contrepoint : un appel à la lenteur, à l’attention, à une présence stylisée au monde. Il invite à penser la montagne non comme un décor à conquérir, mais comme un milieu à composer - une topographie à lire autant qu’à gravir.

En ce sens, Mallory propose moins une thèse qu’un angle, une orientation. Il ouvre un territoire de sens dans lequel l’alpinisme devient un langage, une poétique gestuelle, une forme de dessin éphémère inscrit dans le rocher. Et il nous rappelle, en creux, que parfois le sommet importe moins que la manière de s’y rendre - ou même que le fait d’y aller du tout.

I SEEM to distinguish two sorts of climber, those who take a high line about climbing and those who take no particular line at all. It is depressing to think how little I understand either, and I can hardly believe that the second sort are such fools as I imagine. Perhaps the distinction has no reality; it may be that it is only a question of attitude. Still, even as an attitude, the position of the first sort of climber strikes a less violent shock of discord with mere reason. Climbing for them means something more than a common amusement, and more than other forms of athletic pursuit mean to other men; it has a recognised importance in life. If you could deprive them of it they would be conscious of a definite degradation, a loss of virtue. For those who take the high line about it climbing may be one of the modern ways of salvation along with slumming, statistics, and other forms of culture, and more complete than any of these. They have an arrogance with regard to this hobby never equalled even by a little king among grouse-killers. It never, for instance, presents itself to them as comparable with field sports. They assume an unmeasured superiority. And yet—they give no explanation.

I am myself one of the arrogant sort, and may serve well for example, because I happen also to be a sportsman. It is not intended that any inference as to my habits should follow from this premise. You may easily be a sportsman though you have never walked with a gun under your arm nor bestrid a tall horse in your pink. I am a sportsman simply because men say that I am ; it would be impossible to convince them of the contrary, and it's no use complaining; and, once I have humbly accepted my fate and settled down in this way of life, I am proud to show, if I can, how I deserve the title. Though a sportsman may be guiltless of sporting deeds, one who has acquired the sporting reputation will show cause in kind if he may. Now, it is abundantly clear that any expedition on the high Alps is of a sporting nature; it is almost aggressively sporting. And yet it would never occur to me to prove my title by any reference to mountaineering in the Alps, nor would it occur to any other climber of the arrogant sort who may also be a sportsman. We set climbing on a pedestal above the common recreations of men. We hold it apart and label it as something that has a special value.

This, though it passes with all too little comment, is a plain act of rebellion. It is a serious deviation from the normal standard of rightness and wrongness, and if we were to succeed in establishing our value for mountaineering we should upset the whole order of society, just as completely as it would be upset if a sufficient number of people who claimed to be enlightened were to eat eggs with knives and regard with disdain the poor folk who ate them with spoons.

But there is a propriety of behaviour for rebels as for others. Society can at least expect of rebels that they explain themselves. Other men are exempt from this duty because they use the recognised labels in the conventional ways. Sporting practice and religious observance were at one time placed above, or below, the need of explanation. They were bottled and labelled " Extra dry," and this valuation was accepted as a premise for a priori judgments by society in general. Rebel minorities have sometimes behaved in the same way, and by the very arrogance of their dogmatism have made a revolution. The porridge-with-salt men have introduced a fashion which decrees that it is right to eat salt with porridge, and no less wrong to conceal its true nature by any other disguise than to pass the bottle from left to right instead of oppositewise. This triumph was secured only by self-assured arrogance. But the correct method for rebels is that they set forth their case for the world to see.

Climbers who, like myself, take the high line have much to explain, and it is time they set about it. Notoriously they endanger their lives. With what object? If only for some physical pleasure, to enjoy certain movements of the body and to experience the zest of emulation, then it is not worth while. Climbers are only a particularly foolish set of desperadoes ; they are on the same plane with hunters, and many degrees less reasonable. The only defence for mountaineering puts it on a higher plane than mere physical sensation. It is asserted that the climber experiences higher emotions; he gets some good for his soul. His opponent may well feel sceptical about this argument. He, too, may claim to consider his soul's good when he can take a holiday. Probably it is true of anyone who spends a well-earned fortnight in healthy enjoyment at the seaside that he comes back a better, that is to say a more virtuous man than he went. Ho w are the climber's joys worth more than the seaside ? What are these higher emotions to which he refers so elusively ? And if they really are so valuable, is there no safer way of reaching them ? Do mountaineers consider these questions and answer them again and again from fresh experience, or are they content with some magic certainty born of comparative ignorance long ago ?

It would be a wholesome tonic, perhaps, more often to meet an adversary who argued on these lines. In practice I find that few men ever want to discuss mountaineering seriously. I suppose they imagine that a discussion with me would be unprofitable; and I must confess that if anyone does open the question my impulse is to put him off. I can assume a vague disdain for civilisation, and I can make phrases about beautiful surroundings, and puff them out, as one who has a secret and does not care to reveal it because no one would understand—phrases which refer to the divine riot of Nature in her ecstasy of making mountains.

Thus I appeal to the effect of mountain scenery upon my aesthetic sensibility. But, even if I can communicate by words a true feeling, I have explained nothing. Aesthetic delight is vitally connected with our performance, but it neither explains nor excuses it. No one for a moment dreams that our apparently wilful proceedings are determined merely by our desire to see what is beautiful. The mountain railway could cater for such desires. By providing view-points at a number of stations, and by concealing all signs of its own mechanism. It might be so completely organised that all the aesthetic joys of the mountaineer should be offered to its intrepid ticketholders. It would achieve this object with a comparatively small expenditure of time, and would even have, one might suppose, a decisive advantage by affording to all lovers of the mountains the opportunity of sharing their emotions with a large and varied multitude of their fellow-men. And yet the idea of associating this mechanism with a snow mountain is the abomination of every species of mountaineer. To him it appears as a kind of rape. The fact that he so regards it indicates the emphasis with which he rejects the crude aesthetic reasons as his central defence.

I suppose that, in the opinion of many people who have opportunities of judging, mountaineers have no ground for claiming for their pursuit a superiority as regards the natural beauties that attend it. An d certainly many huntsmen would resent their making any such claim. We cannot, therefore, remove mountaineering from the plane of hunting by a composite representation of its merits—by asserting that physical .and aesthetic joys are blent for us and not for others.

Nevertheless, I a m still arrogant, and still confident in the superiority of mountaineering over all other forms of recreation. But what do I mean by this superiority ? And in what measure do I claim it ? On what level do we place mountaineering ? What place in the whole order of experience is occupied by our experience as mountaineers ? The answer to these questions must be very nearly connected with the whole explanation of our position; it ma y actually be found to include in itself a defence of mountaineering.

It must be admitted at the outset that our periodic literature gives little indication that our performance is concerned no less with the spiritual side of us than with the physical. This is, in part, because we require certain practical information of anyone who describes an expedition. Our journals, with one exception, do not pretend to be elevated literature, but aim only at providing useful knowledge for climbers. With this purpose w e try to show exactly where upon a mountain our course lay, in what manner the conditions of snow and ice and rocks and weather were or were not favourable to our enterprise, and what were the actual difficulties we had to overcome and the dangers we had to meet. Naturally, if we accept these circumstances, the impulse for literary expression vanishes; not so much because the matter is not suitable as because, for literary expression, it is too difficult to handle. A big expedition in the Alps, say a traverse of Mont Blanc, would be a superb theme for an epic poem. But we are not all even poets, still less Homers or Miltons. We do, indeed, possess lyric poetry that is concerned with mountains, and value it highly for the expression of much that we feel about them. But little of it can be said to suggest that mountaineering in the technical sense offers an emotional experience which cannot otherwise be reached. A few essays and a few descriptions do give some indication that the spiritual part of man is concerned. Most of those who describe expeditions do not even treat them as adventure, still less as being connected with any emotional experience peculiar to mountaineering. Some writers, after the regular careful references to matters. of plain fact, insert a paragraph dealing summarily with an aesthetic experience; the greater part make a bare allusion to such feelings or neglect them altogether, and perhaps these are the wisest sort.

And yet it is not so very difficult to write about aesthetic impressions in some way so as to give pleasure. If we do not ask too much, many writers are able to please us in this. respect. We may be pleased, without being stirred to the depths, by anyone who can make us believe that he has. experienced aesthetically; we may not be able to feel with him what he has felt, but if he talks about it simply we may be quite delighted to perceive that he has felt as we too are capable of feeling. Mountaineers who write do not, as a rule, succeed even in this small degree. If they are so bold as to attempt a sunset or sunrise, we too often feel uncertain as, we read that they have felt anything—and this even though we may know quite well that they are accustomed to feel as we feel ourselves.

These observations about our mountain literature are not made by way of censure or in disappointment; they are put forward as phenomena, which have to be explained, not so. much by the nature of mountaineers, but rather by the nature of their performance. The explanation which commends itself to me is derived very simply from the conception of mountaineering, which, expressed or unexpressed, is common, I imagine, to all us of the arrogant sort. W e do not think that our aesthetic experiences of sunrises and sunsets and clouds and thunder are supremely important facts in mountaineering, but rather that they cannot thus be separated and catalogued and described individually as experiences at all They are not incidental in mountaineering, but a vital and inseparable part of it; they are not ornamental, but structural ; they are not various items causing emotion but parts of an emotional whole; they are the crystal pools perhaps, but they owe their life to a continuous stream.

It is this unity that makes so many attempts to describe aesthetic detail seem futile. Somehow they miss the point and fail to touch us. It is because they are only fragments. If we take one moment and present its emotional quality apart from the whole, it has lost the very essence that gave it a value. If we write about an expedition from the emotional point of view in any part of it, we ought so to write about the whole adventure from beginning to end.

A day well spent in the Alps is like some great symphony. Andante, andantissimo sometimes, is the first movement—the grim, sickening plod up the moraine. But how forgotten when the blue light of dawn flickers over the hard, clean snow! The new motif is ushered in, as it were, very gently on the lesser wind instruments, hautboys and flutes, remote but melodious and infinitely hopeful, caught by the violins in the growing light, and torn out by all the bows with quivering chords as the summits, one by one, are enmeshed in the gold web of day, till at last the whole band, in triumphant accord, has seized the air and romps in magnificent frolic, because there you are at last marching, all a-tingle with warm blood, under the sun. And so throughout the day successive moods induce the symphonic whole—allegro while you break the back of an expedition and the issue is still in doubt; scherzo, perhaps, as you leap up the final rocks of the arete or cut steps in a last short slope, with the ice-chips dancing and swimming and bubbling and bounding with magic gaiety over the crisp surface in their mad glissade ; and then, for the descent, sometimes again andante, because, while the summit was still to win, you forgot that the business of descending may be serious and long; but in the end scherzo once more—with the brakes on for sunset.

Expeditions in the Alps are all different, no less than symphonies are different, and each is a fresh experience. Not all are equally buoyant with hope and strength; nor is it only the proportion of grim to pleasant that varies, but no less the quality of these and other ingredients and the manner of their mixing. But every mountain adventure is emotionally complete. The spirit goes on a journey just as does the body, and this journey has a beginning and an end, and is concerned with all that happens between these extremities. You cannot say that one part of your adventure was emotional while another was not, any more than you can say of your journey that one part was travelling and another was not. You cannot subtract parts and still have the whole. Each part depends for its value upon all the other parts, and the manner in which it is related to them. The glory of sunrise in the Alps is not independent of what has passed and what's to come ; without the day that is dying and the night that is to come the reverie of sunset would be less suggestive, and the deep valley-lights would lose their promise of repose. Still more, the ecstasy of the summit is conditioned by the events of getting up and the prospects of getting down.

Mountain scenes occupy the same place in our consciousness with remembered melody. It is all one whether I find myself humming the air of some great symphonic movement or gazing upon some particular configuration of rock and snow, or peak and glacier, or even more humbly upon some colour harmony of meadow and sweet pinewood in Alpine valley. Impressions of things seen return unbidden to the mind, so that we seem to have whole series of places where we love to spend idle moments, inns, as it were, inviting us by the roadside, and many of them pleasant and comfortable Gorphwysfas, so well known to us by now that we make the journey easily enough with a homing instinct, and never feel a shock of surprise, however remote they seem, when we find ourselves there. Many people, it appears, have strange dreamlands, where they are accustomed to wander at ease, where no " dull brain perplexes and retards," nor tired body and heavy limbs, but where the whole emotional being flows, unrestrained and unencumbered, it knows not whither, like a stream rippling happily in its clean sandy bed, careless towards the infinite. My own experience has more of the earth. My mental homes are real places, distinctly seen and not hard to recognise. Only a little while ago, when a sentence I was writing got into a terrible tangle, I visited one of them. A n infant river meanders coolly in a broad, grassy valley; it winds along as gently almost as some glassy snake of the plains, for the valley is so flat that its slope is imperceptible. The green hills on either side are smooth and pleasing to the eye, and eventually close in, though not completely. Here the stream plunges down a steep and craggy hillside far into the shadow of a deeper valley. You may follow it down by a rough path, and then, turning aside, before you quite reach the bottom of the second valley, along a grassy ledge, you may find a modest inn. The scene was visited in reality by three tired walkers at the end of a first day in the Alps a few seasons back. It is highly agreeable. When I discover myself looking again upon the features of this landscape, I walk no longer in a vain shadow, disquieting myself, but a delicious serenity embraces my whole being. In another scene which I still sometimes visit, though not so often as formerly, the main feature is a number of uniform truncated cones with a circular base of, perhaps, 8 in. diameter; they are made of reddish sand. They were, in fact, made long ago by filling a flower-pot with sandy soil from the country garden where I spent a considerable part of my childhood. The emotional quality of this scene is more exciting than that of the other. It recalls the first occasion upon which I made sand-pies, and something of the creative force of that moment is associated with the tidy little heaps of reddish sand.

For any ardent mountaineer whose imaginative parts are made like mine, normally, as I should say, the mountains will naturally supply a large part of this hinterland, and the more important scenes will probably be mountainous—an indication in itself that the mountain experiences, unless they are merely terrible, are particularly valuable.

It is difficult to see why certain moments should have this queer vitality, as though the mind's home contained some mystic cavern set with gems which wait only for a gleam of light to reveal their hidden glory. What principle is it that determines this vitality? Perhaps the analogy with musical experience ma y still suffice. Mountain scenes appear to recur, not only in the same quality with tunes from a great work, say, Mozart or Beethoven, but from the same differentiating cause. It is not mere intensity of feeling that determines the places of tunes in my subconscious self, but chiefly some other principle. When the chords of melody are split, and unsatisfied suggestions of complete harmony are tossed among the instruments; when the firm rhythm is lost in remote pools and eddies, the mind roams perplexed ; it experiences remorse and associates it with no cause; grief, and it names no sad event; desires crying aloud and unfulfilled, and yet it will not formulate the object of them; but when the great tide of music rises with a resolved purpose, floating the strewn wreckage and bearing it up together in its embracing stream, like a supreme spirit in the glorious act of creation, then the vague distresses and cravings are satisfied, a divine completeness of harmony possesses all the senses and the mind as though the universe and the individual were in exact accord, pursuing a common aim with the efficiency of mechanical perfection. Similarly, some parts of a climbing day give us the feeling of things unfulfilled; w e doubt and tremble; w e go forward not as me n determined to reach a fixed goal; our plans do not convince us and miscarry; discomforts are not willingly accepted as a proper necessity; spirit and body seem to betray each other: but a time comes when all this is changed and w e experience a harmony and a satisfaction. T h e individual is in a sense submerged, yet not so as to be less conscious; rather his consciousness is specially alert, and he comes to a finer realisation of himself than ever before. It is these moments of supremely harmonious experience that remain always with us and part of us. Other times and other scenes besides may be summoned back to gleam across the path, elusive revenants; but those that are born of the supreme accord are more substantial; they are the real immortals. Sensation may fill the mind with melody remembered, so that the great leading airs of a symphony become an emotional commonplace for all who have heard it, and for mountaineers it may with no less facility evoke a mountain scene.

But once again. What is the value of our emotional experience among mountains? W e may show by comparison the kind of feeling we have, but might not that comparison be applied with a similar result in other spheres ?

How it would disturb the cool contempt of the arrogant mountaineer to whisper in his ear, " Why not drop it and take up, say. Association football ?" Not, of course, if a footballer made the remark, because the mountaineer would merely humour him as he would humour a child. That, at least, is the line I should take myself, and I can't imagine that, for instance, a proper president of the Alpine Club, if approached in this way by the corresponding functionary of the A.F.A., could adopt any other. But supposing a member of the club were to make the suggestion—with the emendation, lest this should be ridiculous, of golf instead of football—imagine the righteousness of his wrath and the majesty of his anger! And yet it is as well to consider whether the footballers, golfers, etc., of this world have not some experience akin to ours. The exteriors of sportsmen are so arranged as to suggest that they have not; but if we are to pursue the truth in a whole-hearted fashion we must, at all costs, go further and see what lies beyond the faces and clothes of sporting men. Happily, as a sportsman myself, I know what the real feelings of sportsmen are; it is clear enough to me that the great majority of them have the same sort of experience as mountaineers.

It is abundantly clear to me, and even too abundantly. The fact that sportsmen are, with regard to their sport, highly emotional beings is at once so strange and so true that a lifetime might well be spent in the testing of it. Very pleasant it would be to linger among the curious jargons, the outlandish manners—barbaric heartiness, mediaeval chivalry, " side " and " swank," if these can be distinguished, in their various appearances—and the mere facial expressions &f the different species in the genus; and to see how all alike have one main object, to disguise the depth of their real sentiment. But these matters are to be enjoyed and digested in the plenty of leisure hours, and I must put them by for now. The plain facts are sufficient for this occasion. Th e elation of sportsmen in success,- their depression in failure, their long-spun vivacity in anecdote—these are the great tests, and by their quality may be seen the elemental play of emotions among all kinds of sportsmen. The footballers, the cricketers, the golfers, the batters and bailers—to be short, of all the one hundred and thirty-one varieties, .all dream by day and by night as the climber dreams. Spheroidic prodigies are immortal each in its locality. The place comes back to the hero with the culminating event—the moment when a round, inanimate object was struck supremely well; and all the great race of hunters, in more lands than one, the me n who hunt fishes and fowls and beasts after their kind, from perch to spotted seaserpent, fat pheasant to dainty lark or thrush, tame deer to jungle-bred monster, all hunters dream of killing animals, whether they be small or great, and whether they be gentle or ferocious. Sport is for sportsmen a part of their emotional experience, as mountaineering is for mountaineers.

How, then, shall we distinguish emotionally between the mountaineer and the sportsman ?

The great majority of men are in a sense artists ; some are active and creative, and some participate passively. No doubt those who create differ in some way fundamentally from those who do not create ; but they hold this artistic impulse in common: all alike desire expression for the emotional side of their nature. The behaviour of those who are devoted to the higher forms of Art shows this clearly enough. It is clearest of all, perhaps, in the drama, in dancing, and in music. Not only those who perform are artists, but also those wh o are moved by the performance. Artists, in this sense, are not distinguished by the power of expressing emotion, but the power of feeling that emotional experience out of which Art is made. We recognise this when w e speak of individuals as artistic, though they have no pretension to create Art. Arrogant mountaineers are all artistic, independently of any other consideration, because they cultivate emotional experience for its own sake; and so for the same reason are sportsmen. It is not paradoxical to assert that all sportsmen—real sportsmen, I mean—are artistic; it is merely to apply that term logically, as it ought to be applied. A large part of the human race is covered in this way by an epithet usually vague and specialised, and so it ought to be. No difference in kind divides the individual who is commonly said to be artistic from the sportsman who is supposed not so to be. On the contrary, the sportsman is a recognisable kind of artist. So soon as pleasure is being pursued, not simply for its face value, as it is being pursued at this moment by the cook below, who is chatting with the fishmonger when I know she ought to be basting the joint, not in the simplest way, but for some more remote and emotional object, it partakes of the nature of Art. This distinction ma y easily be perceived in the world of sport. It points the difference between one who is content to paddle a boat by himself because he likes the exercise, or likes the sensation of occupying a boat upon the water, or wants to use the water to get to some desirable spot, and one who trains for a race; the difference between kicking a football and playing in a game of football; the difference between riding individually for the liver's sake and riding to hounds. Certainly neither the sportsman nor the mountaineer can be accused of taking his pleasure simply. Both are artists ; and the fact that he has in view an emotional experience does not remove the mountaineer even from the devotee of Association football.

But there is Art and ART . W e ma y distinguish amongst artists. Without an exact classification or order of merit w e do so distinguish habitually. The " Fine Arts " are called " fine " presumably because we consider that all Arts are not fine. The epithet artistic is commonly limited to those who are seen to have the artistic sense developed in a peculiar degree.

It is precisely in making these distinctions that we may estimate what we set out to determine—the value of mountaineering in the whole order of our emotional experience. To what part of the artistic sense of man does mountaineering belong ? To the part that causes him to be moved by music or painting, or to the part that makes him enjoy a game?

By putting the question in this form we perceive at once the gulf that divides the arrogant mountaineer from the sportsman. It seemed perfectly natural to compare a day in the Alps with a symphony. For mountaineers of my sort mountaineering is rightfully so comparable; but no sportsman could or would make the same claim for cricket or hunting, or whatever his particular sport might be. He recognises the existence of the sublime in great Art, and knows, even if he cannot feel, that its manner of stirring the heart is altogether different and vaster. But mountaineers do not admit this difference in the emotional plane of mountaineering and Art. They claim that something sublime is the essence of mountaineering. They can compare the call of the hills to the melody of wonderful music, and the comparison is not ridiculous.

Version française :

Je crois distinguer deux types d'alpinistes : ceux qui ont une haute idée de leur activité et ceux qui ne lui accordent pas une importance particulière. Il m'est déprimant de voir combien je les comprends peu, les uns comme les autres, et j'ai peine à croire que les seconds soient aussi stupides que je l'imagine. Peut-être qu'il ne s'agit que d'une question d'attitude. Mais si tel est le cas, celle des alpinistes du premier genre heurte moins violemment la raison. Pour eux, grimper est plus qu'un simple divertissement, grimper a plus de sens que d'autres formes d'activités sportives peuvent en avoir pour les autres hommes ; grimper a une importance reconnue dans la vie. Si on pouvait les en priver, ils le vivraient comme une dégradation, une perte de valeur. Pour ceux qui s'en font une haute idée, l'alpinisme peut être l'une des voies modernes de salut, au même titre que le baguenaudage, les statistiques et d'autres formes de culture, et plus complètement qu'aucune d'entre elles. Ils ont à l'égard de ce passe-temps une arrogance que rien n'égale, pas même celle du plus fier des tueurs de tétras. Il ne leur viendrait jamais à l'esprit de le comparer aux sports collectifs. Ils ont un incommensurable sentiment de supériorité. Pourtant, ils n'expliquent rien. Je suis moi-même du type arrogant et je peux facilement servir d'exemple, car il se trouve que je suis aussi un sportif. Cette qualité n'interfère en rien avec mes habitudes : on peut aisément être un sportif sans n'avoir jamais marché avec un fusil sous le bras ou monté à cheval avec grâce. Je suis un sportif simplement parce que mes congénères disent que je le suis ; il serait impossible de les convaincre du contraire, et s'en plaindre ne sert à rien ; ayant humblement accepté mon sort, bien installé dans ce mode de vie, je suis fier de montrer, si j'en suis capable, combien je mérite ce titre. Même si un sportif peut être vierge de résultats, celui qui a acquis une telle réputation en fera la preuve s'il le peut. Or, il est évident que toute expédition dans les Alpes est de nature sportive - presque agressivement sportive. Et pourtant, il ne me viendrait jamais à l'idée de prouver mon titre par une quelconque référence à l'alpinisme dans les Alpes, pas plus qu'à aucun autre alpiniste du type arrogant qui s'avérerait être aussi un sportif. Nous plaçons l'alpinisme sur un piédestal, au-dessus des récréations communes des hommes. Nous le classons à part, nous lui accordons une valeur particulière. Il s'agit, on le dit trop peu, d'un authentique acte de rébellion, d'un écart sérieux au regard des normes acceptées. Si nous pouvions établir notre valeur en alpinisme, nous bouleverserions l'ordre social tout aussi radicalement que si un nombre suffisant de prétendus éclairés se mettaient à manger les œufs avec un couteau et à mépriser les pauvres types qui le font avec une cuillère. Mais les rebelles, eux aussi, doivent respecter certaines convenances. La société attend d'eux, a minima, qu'ils s'expliquent. D'autres sont exemptés de cette obligation, car ils utilisent des labels reconnus. Les pratiques sportives et religieuses se situaient autrefois au-dessus, ou au-dessous, de tout besoin d'explication. On les mettait en bouteille, on les étiquetait « extra-dry », et cette évaluation était acceptée comme préliminaire d'un jugement a priori par la société en général. Certaines minorités rebelles se sont parfois comportées de la même manière et, par l'arrogance même de leur dogmatisme, ont fait une révolution. Les partisans du porridge salé ont créé une mode selon laquelle il est tout aussi juste d'ajouter du sel dans son porridge que de cacher sa véritable nature en passant la bouteille de gauche à droite plutôt que l'inverse. Ce triomphe n'a été obtenu que par une arrogance assumée. Cependant, la bonne méthode pour les rebelles consiste à présenter des arguments au monde. Les alpinistes qui, comme moi, empruntent la voie haute ont beaucoup à expliquer, et il est temps qu'ils s'y mettent. Il est notoire qu'ils mettent leur vie en danger. Pour quelle raison ? S'il ne s'agit que de plaisir physique, du goût du corps en mouvement et d'un zeste d'émulation, cela n'est pas digne d'intérêt. Les alpinistes ne sont qu'un groupe de desperados particulièrement stupides ; ils sont sur le même plan que les chasseurs, et à bien des degrés moins raisonnables. La seule façon de défendre l'alpinisme, c'est de le placer sur un plan supérieur, au-dessus de la simple sensation physique. On affirmera que l'alpiniste éprouve des émotions plus élevées; qu'il fait du bien à son âme. Son adversaire se montrera sceptique quant a cet argument. Lui aussi peut prétendre au bien de son âme lorsqu'il prend des vacances. Il est probable que celui qui s'offre deux semaines de réjouissances saines et méritées en bord de mer reviendra meilleur, c'est-à-dire dans une condition plus vertueuse qu'au départ. En quoi les joies de l'alpiniste sont-elles plus précieuses? Quelles sont ces émotions supérieures auxquelles il se réfère de manière si insaisissable ?.Et si elles ont tant de valeur, n'existe-t-il pas un moyen plus sûr de les atteindre? Les alpinistes réfléchissent-ils à ces questions? Cherchent-ils à y répondre en partant sans cesse vers de nouvelles expériences ou se contentent-ils de certitudes magiques ancrées dans de vieilles ignorances ? Il serait très stimulant de rencontrer plus souvent un adversaire qui argumenterait sur ces questions. Dans la pratique, j'observe que peu d'hommes souhaitent discuter sérieusement de l'alpinisme. Je suppose qu'ils s'imaginent qu'une discussion avec moi ne serait pas profitable; et je dois avouer que si quelqu'un aborde cette question, mon instinct est de le décourager. Je suis capable de professer un vague mépris pour la civilisation, de m'en tirer avec quelques phrases sur la beauté des paysages et le désordre divin de la Nature dans sa création extatique des montagnes, de les renvoyer dans leurs cordes pour ne pas révéler un secret que personne ne comprendrait. En cela, je fais appel à l'effet des paysages de montagne sur ma sensibilité esthétique. Je peux communiquer par des mots un sentiment vrai, mais je n'explique rien. Le plaisir esthétique est au cœur de nos entreprises, mais il ne saurait les expliquer ni les excuser. Personne ne peut envisager un seul instant que nos actions soient simplement déterminées par notre désir de voir la beauté. Le chemin de fer en montagne pourrait combler de tels souhaits. En proposant des points de vue à chaque arrêt et en dissimulant tous les signes de sa mécanique, il pourrait être si parfaitement organisé que toutes les joies esthétiques de l'alpiniste seraient offertes à ses intrépides détenteurs de billets. Il permettrait ainsi d'atteindre ce but en un temps relativement réduit, et offrirait même l'occasion aux vrais amoureux de la montagne de partager leurs émotions avec une multitude de leurs semblables. Et pourtant, l'idée d'associer cette mécanique à une montagne enneigée est une abomination pour tout alpiniste, une sorte de viol - ce qui montre à quel point il refuse de faire des pures raisons esthétiques sa motivation première. Je suppose que, pour ceux qui sont en position d'en juger, les alpinistes n'ont aucun titre à prétendre que leur quête offre, plus que toute autre, accès aux beautés de la nature. De nombreux chasseurs seraient certainement heurtés par une telle affirmation. On ne peut donc pas distinguer l'alpinisme de la chasse en vantant ses mérites composites et en affirmant que ces joies physiques et esthétiques nous sont réservées. Quoi qu'il en soit, je reste arrogant, et convaincu de la supériorité de l'alpinisme sur toutes les autres formes de loisirs. Mais qu'est-ce que cette supériorité signifie pour moi ? Et dans quelle mesure dois-je y prétendre? À quel niveau place-t-on l'alpinisme? Quelle place notre expérience d'alpiniste occupe-t-elle dans l'ordre de l'expérience en général? La réponse à ces questions doit être étroitement liée à l'explication globale de notre position; elle pourrait constituer en elle-même une défense de l'alpinisme. Il faut admettre d'emblée que nos publications périodiques - donnent peu d'indications sur le fait que nos performances ont une dimension spirituelle autant que physique. Cela tient en partie à ce que nous exigeons certaines informations pratiques de la part de quiconque décrit une ascension'. Nos revues, à une exception près, ne prétendent pas être de la littérature de haut niveau, mais visent uniquement à fournir des connaissances utiles aux alpinistes. Dans ce but, nous essayons de montrer avec exactitude où se trouvait notre voie sur une montagne, de quelle manière les conditions de neige, de glace, de rocher et la météo étaient ou non favorables à notre entreprise, quelles étaient les difficultés réelles que nous avons dû surmonter et les dangers auxquels nous devions faire face. Naturellement, si nous acceptons ces contraintes, l'impulsion littéraire disparaît; non pas tant parce que le sujet ne s'y prête pas, mais plutôt parce que, pour l'expression littéraire, il est trop difficile à traiter.

Une grande ascension dans les Alpes, par exemple une traversée du mont Blanc, serait un superbe thème pour un poème épique. Mais nous ne sommes pas tous poètes, encore moins Homère ou Milton. Certes, nous savons trouver des élans lyriques et poétiques pour exprimer ce que nous ressentons face aux montagnes, et nous en usons avec plaisir. Mais rien ou presque de tout cela ne suggère que l'alpinisme, au sens technique du terme, offre une expérience émotionnelle qui ne peut pas être atteinte autrement. Quelques essais et quelques descriptions abordent timidement cette dimension spirituelle. Mais la plupart de ceux qui décrivent des ascensions n'y voient aucune aventure, aucune dimension émotionnelle propre à l'alpinisme. Certains auteurs, après les références inévitables et minutieuses aux faits, insèrent un paragraphe traitant sommairement d'une expérience esthétique; la plupart font une simple allusion à de tels sentiments ou les négligent complètement, et ce sont peut-être les plus sages. Pourtant, il n'est pas si difficile d'écrite sur des impressions esthétiques de manière à partager ce plaisir. Si l'on n'en demande pas trop, bien des écrivains sont capables de nous satisfaire à cet égard. Nous pourrions être comblés, sans être émus aux tréfonds, par qui saurait nous transmettre ce qu'il a éprouvé esthétiquement; sans forcément partager avec lui tout ce qu'il a vécu, nous pourrions, s'il en parle simplement, être simplement heureux de voir qu'il a ressenti ce que nous aussi sommes capables de ressentir. Mais les alpinistes qui écrivent ne réussissent généralement pas, même dans une si faible mesure. S'ils ont l'audace de tenter un coucher ou un lever de soleil, nous doutons trop souvent en les lisant qu'ils aient ressenti quoi que ce soit - et cela, même si nous savons qu'ils sont accoutumés à ressentir ce que nous ressentons nous-mêmes. Ces observations sur notre littérature de montagne ne sont pas faites sous le coup de la déception; il faut les énoncer et tenter d'expliquer le phénomène non pas tant par la nature des alpinistes que par la nature de leurs performances. L'explication qui s'impose à moi découle très simplement d'une conception de l'alpinisme qui, exprimée ou non, est commune, j'imagine, à tous les arrogants que nous sommes. Nos expériences esthétiques des levers et couchers de soleil, des nuages et de l'orage ne nous semblent pas être des faits d'une suprême importance en termes d'alpinisme; il nous est impossible de les isoler, de les cataloguer et de les décrire individuellement comme des expériences. Pourtant, elles ne sont pas accessoires en alpinisme, mais en constituent une partie vitale et indissociable du tout ; elles ne sont pas ornementales, mais structurelles; ce ne sont pas des éléments épars déclenchant des émotions, elles forment un ensemble émotionnel cohérent. Ce sont des bassins d'eaux cristallines qui n'existent que par le courant qui les traverse. C'est cette unité qui rend vaines tant de tentatives de description des détails esthétiques qui passent à côté de l'essentiel et ne nous touchent pas. C'est parce qu'il ne s'agit que de fragments. Si nous nous arrêtons pour isoler la qualité émotionnelle d'un moment, il perd l'essence même de ce qui faisait sa valeur. Si l'on prend le point de vue des émotions pour écrire un quelconque moment d'une ascension, il faut écrire ainsi sur toute l'aventure, du début a la fin. Une belle journée passée dans les Alpes est comme une grande symphonie, Andante, andantissimo, tel est parfois le premier mouvement - la marche nocturne, sévère et nauséeuse, sur les moraines. Mais comme c'est vite oublié lorsque la lumière bleue de l'aube scintille sur la neige dure et immaculée ! Le nouveau motif est introduit tout en douceur par les petits instruments à vent, hautbois et flûtes, lointains, mélodieux et porteurs d'infinis espoirs, repris par les violons dans la lumière qui s'affirme puis par tous les archets en accords frémissants tandis que la toile d'or du jour se pose sur les sommets, un à un, jusqu'à ce que l'orchestre, en accord triomphant, s'empare du thème dans un élan magnifique, car vous voilà enfin en marche sous le soleil, frissonnant d'émotion et du sang chaud circulant dans les veines. Ainsi, au long de la journée, des humeurs successives balayent tout le spectre symphonique - allegro quand le plus dur est passé mais que l'issue de la course est encore incertaine; scherzo, peut-être, quand vous sautez sur les rochers de l'arête sommitale ou taillez des marches dans un dernier ressaut, que les éclats de glace voltigent sur la surface croustillante dans une danse joyeuse et magique avant de plonger dans une folle glissade ; et puis, à la descente, andante parfois encore, parce qu'on a oublié qu'elle pouvait être longue, sérieuse tant que le sommet était encore en ligne de mire; mais a la fin, scherzo encore une fois - et un dernier silence pour le coucher du soleil. Les ascensions dans les Alpes, comme les symphonies, sont toutes différentes, et chacune est une expérience nouvelle. Toutes ne sont pas aussi chargées d'espoir et de force; la part du sombre et du plaisir varie, ainsi que la qualité de ces ingrédients et la manière de les mélanger. Chaque aventure en montagne est émotionnellement complète. L'esprit part en voyage autant que le corps; ce voyage a un début et une fin, tout ce qui se passe entre ces deux moments en fait la saveur. Vous ne pouvez pas dire qu'une partie de votre aventure a été émotionnelle tandis qu'une autre ne l'a pas été, vous ne pouvez pas dire de votre aventure qu'une partie a été un voyage et une autre ne l'a pas été. Vous ne pouvez pas extraire des parties et conserver le tout. La valeur de chaque partie dépend de toutes les autres parties et de la manière dont elle leur est liée, La gloire d'un lever du soleil sur les Alpes n'est pas indépendante de ce qui s'est passé et de ce qui va arriver; sans le jour qui se meurt et la nuit qui va venir, la rêverie du coucher du soleil serait moins suggestive, et les lumières lointaines de la vallée perdraient leur promesse de repos. L'extase du sommet est conditionnée par les événements de l'ascension et les perspectives de descente. Les scènes de montagne occupent la même place dans notre conscience qu'une mélodie mémorisée. Il y a une unité entre fredonner l'air d'un grand mouvement symphonique et contempler une formation de roche et de neige, un pic et un glacier, ou plus humblement l'harmonie de couleurs des prés et des pinèdes dans une vallée alpine. Les impressions des choses vues reviennent spontanément à l'esprit pour nous offrir une série d'endroits où nous aimons passer des moments de farniente, comme des auberges accueillantes au bord de la route; beaucoup de ces lieux, Gorffwysfas 2 agréables et confortables, nous les connaissons si bien que le voyage est facile, on s'y sent à la maison et, aussi lointains qu'ils puissent paraître, on n'est jamais surpris de s'y retrouver. Nombreux sont ceux, semble-t-il, qui connaissent ces étranges pays oniriques où l'on erre à sa guise sans que « l'esprit lourd hésite et paresse », où l'on ne connait ni fatigue du corps ni jambes de plomb, mais ou tout l'être émotionnel coule sans but connu, sans retenue et sans entrave, comme un ruisseau serpentant joyeusement dans son lit sablonneux, clair, insouciant, vers l'infini. Ma propre expérience est plus terrestre. Les foyers de mon esprit sont des lieux réels, vus distinctement et faciles à reconnaître. Récemment encore, alors qu'une phrase que je tentais d'écrire s'embrouillait sous mes doigts, j'ai visité l'un d'eux. Près de sa source, un ruisseau étire tranquillement ses méandres dans une large vallée d'alpage; il serpente doucement, comme un luisant serpent des plaines, car la pente est imperceptible.

Les sommets verdoyants alentour, doux et agréables à l'œil, se rapprochent peu à peu, jusqu'au point où le torrent plonge dans un versant abrupt vers l'ombre lointaine d'une vallée profonde. On peut le suivre par un sentier escarpé, puis bifurquer vers une vire herbeuse peu avant d'atteindre le fond de la seconde vallée où se trouve peut-être une modeste auberge. La scène a été visitée en réalité par trois marcheurs fatigués à la fin d'une première journée dans les Alpes il y a quelques saisons. Elle est agréable au plus haut point. Quand je me retrouve à contempler à nouveau les traits de ce paysage, je ne marche plus, inquiet, dans l'ombre vaine, mais une délicieuse sérénité envahit tout mon être. Dans une autre scène qu'il m'arrive encore de visiter, quoique moins souvent qu'autrefois, l'élément principal est une série de cônes tronqués de sable rougeâtre, tous identiques, d'une vingtaine de centimètres de diamètre. Ils ont été fabriqués il y a bien longtemps en remplissant un pot de fleurs avec la terre sableuse du jardin de campagne ou j'ai passé une grande partie de mon enfance. La qualité émotionnelle de cette scène est plus excitante que celle de l'autre. Elle me rappelle la première fois où j'ai fait des châteaux de sable, et quelque chose de la force créatrice de ce moment est associé aux petits tas bien alignés de sable rouge. Pour tout alpiniste passionné dont l'imagination est faite comme la mienne, normalement, devrais je dire, les montagnes alimenteront naturellement une grande partie de cet arrière pays, et les scènes les plus importantes s'y dérouleront probablement - une indication en soi que les expériences en montagne, à moins qu'elles ne soient simplement terribles, sont particulièrement précieuses. Il est difficile de comprendre pourquoi certains moments ont cette étrange vitalité, comme si la demeure de l'esprit recelait quelque caverne mystique sertie de gemmes n'attendant qu'un rayon de lumière pour révéler leur gloire cachée. Quel est le principe qui détermine cette vitalité ? Peut-être que l'analogie avec l'expérience musicale suffit encore. Les scènes de montagne semblent nous revenir en mémoire avec la qualité d'une mélodie de Mozart ou de Beethoven, et pour une même cause singulière. Ce n'est pas seulement l'intensité du sentiment qui détermine la place des mélodies dans mon subconscient mais, au premier chef, un autre principe. Lorsque les accords de la mélodie s'éloignent, que l'harmonie peine à s'installer entre les instruments, quand le rythme hésite, se perd dans des tourbillons lointains, l'esprit vagabonde, perplexe. Il éprouve des remords sans les associer à aucune cause ; du chagrin, sans identifier aucun événement triste ; d'intenses désirs inassouvis dont il ne formule pas l'objet ; mais lorsque la grande vague musicale s'élève dans un dessein résolu, soulevant les débris flottant pour les entraîner dans un même courant comme un esprit suprême dans l'acte glorieux de la création, alors les frustrations se dissolvent et les désirs sont satisfaits, la divine complétude de l'harmonie s'empare des sens et de l'esprit comme si l'univers et l'individu étaient en parfait accord, travaillant pour un but commun avec une perfection mécanique. De la même façon, certaines parties d'une journée en montagne peuvent nous laisser un sentiment d'inachevé ; nous doutons et tremblons; nous n'avançons pas comme des hommes déterminés à atteindre leur but ; nos plans fragiles échouent ; l'inconfort n'est plus accepté comme une vraie nécessité ; l'esprit et le corps semblent se trahir l'un l'autre : mais il arrive un moment où tout cela change, où nous retrouvons l'harmonie et la satisfaction. Alors l'individu est, en quelque sorte, submergé, non qu'il soit moins conscient, au contraire, sa conscience est particulièrement alerte et il parvient à une meilleure réalisation de lui-même que jamais auparavant. Ces moments d'expérience suprêmement harmonieuse ne nous quitteront plus, ils feront partie de nous. D'autres époques et d'autres scènes peuvent être convoquées pour éclairer notre chemin comme des revenants insaisissables; mais ceux qui naissent de l'accord suprême sont plus substantiels ; ce sont les vrais immortels. La sensation peut offrir à l'esprit des mélodies que l'on mémorise comme les grands airs d'une symphonie, nos lieux communs émotionnels. Pour les alpinistes, elle peut convoquer aussi aisément une scène de montagne. Mais encore une fois. Quelle est la valeur de notre expérience émotionnelle en montagne? Nous pouvons user de comparaisons pour montrer le sentiment que nous éprouvons, mais cette comparaison ne pourrait-elle pas s'appliquer avec un résultat similaire à d'autres domaines ? Comme il serait troublé dans son froid mépris, l'alpiniste arrogant, si on lui murmurait à l'oreille : « Pourquoi ne pas laisser tomber et te lancer, disons, dans le football? » Si la remarque émanait d'un footballeur, l'alpiniste la prendrait bien sûr à la plaisanterie. C'est du moins la ligne que j'adopterais moi-même, et je ne peux pas imaginer que, par exemple, un président de l'Alpine Club, s'il était ainsi sollicité par le fonctionnaire correspondant de la Football Association, puisse en adopter une autre. Mais supposons que la suggestion soit le fait d'un membre du Club - en remplaçant le football par le golf pour éviter le ridicule -, imaginez la juste et majestueuse colère de l'intéressé ! Et pourtant il convient de se demander si les footballeurs, les golfeurs, etc., de ce monde n'ont pas une expérience semblable à la nôtre. L'équipement des sportifs est fait pour suggérer que ce n'est pas le cas; mais si nous voulons rechercher la vérité de tout notre cœur, nous devons à tout prix aller plus loin, voir ce qui se cache au-delà des visages et de l'habit, Heureusement, étant moi-même sportif, je connais leurs véritables sentiments; il me paraît évident que la grande majorité d'entre eux ont des expériences similaires à celles des alpinistes.

C'est tout à fait clair pour moi, et même trop. Le fait que les sportifs deviennent des êtres si émotionnels quand il s'agit de leur sport est à la fois si étrange et si vrai qu'on pourrait passer sa vie à le vérifier. On s'attarderait avec plaisir sur les curiosités du jargon, les manières extravagantes - cordialité barbare, esprit chevaleresque sincère ou non.. si tant est qu'il existe une différence - ou les expressions faciales des différentes espèces du genre. On voit alors combien tous ont un même objectif: dissimuler la profondeur de leurs sentiments réels. Mais il faudrait du temps pour apprécier ces questions à leur juste mesure, et je dois les mettre de côté pour le moment. Les simples faits me suffisent ici. L'exaltation des sportifs face au succès, leur dépression dans l'échec, leur vivacité bavarde dans l'anecdote - tels sont les grands symptômes qui donnent à voir le jeu élémentaire des émotions chez tous les types de pratiquants. Les footballeurs, les joueurs de cricket, les golfeurs, tous ceux qui lancent ou frappent des balles.. bref les cent trente et une espèces de sportifs rêvent jour et nuit comme rêve l'alpiniste. Les prodiges sphéroïdes sont immortels, chacun en sa paroisse. Le titre revient au héros qui, au culmen de l'événement, frappe avec une suprême habileté un objet rond et inanimé. Et toute la grande race de chasseurs, dans plus d'un pays, les hommes qui chassent les poissons, les oiseaux et les bêtes selon leur espèce, de la perche à l'anguille tachetée, du gras faisan à l'alouette ou la grive délicate, du cerf de la forêt voisine au monstre de la jungle, tous les chasseurs rêvent de tuer des animaux petits ou grands, doux ou féroces. Le sport fait partie de l'expérience émotionnelle des sportifs, comme l'alpinisme pour les alpinistes. Comment alors distinguer émotionnellement l'alpiniste du sportif ? La grande majorité des hommes sont, en un sens, artistes ; certains sont actifs et créatifs, d'autres s'expriment passivement.

Il ne fait aucun doute que ceux qui créent diffèrent fondamentalement de ceux qui ne créent pas ; mais ils ont en commun cet élan artistique: tous désirent exprimer le côté émotionnel de leur nature. Le comportement de ceux qui se consacrent aux formes supérieures de l'art le montre bien. C'est peut-être dans les arts de la scène, théâtre, danse, musique que cela est le plus clair. Sont artistes non seulement ceux qui jouent, mais aussi ceux qui sont émus par le spectacle. Les artistes, en ce sens, ne se distinguent pas par le pouvoir d'exprimer des émotions, mais par le pouvoir de ressentir cette expérience émotionnelle à partir de laquelle l'Art est fait. Nous le reconnaissons lorsque nous qualifions certains individus d'artistiques, même s'ils n'ont aucune prétention à créer de l'Art. Les alpinistes arrogants sont tous artistiques, indépendamment de toute autre considération, car ils cultivent l'expérience émotionnelle pour elle-même ; et les sportifs le sont pour la même raison. Il n'est pas paradoxal d'affirmer que tous les sportifs - les vrais sportifs, je veux dire - sont artistiques; il s'agit simplement d'utiliser ce terme logiquement, comme il doit l'être. Une grande partie du genre humain est concernée par cette épithète à la fois vague et spécialisée. Aucune différence de nature ne sépare l'individu que l'on dit communément artistique du sportif que l'on suppose ne pas trop l'être. Au contraire, le sportif est un type d'artiste reconnaissable. Des que le plaisir est recherché non pas pour sa satisfaction directe - comme il l'est en ce moment par la cuisinière d'en bas, qui discute avec la poissonnière alors que je sais qu'elle devrait arroser le rôti -, mais pour un objet plus lointain et émotionnel, il participe de la nature de l'Art. Cette distinction peut aisément être perçue dans le monde du sport. Elle correspond à la différence entre celui qui se satisfait d'aller ramer parce qu'il aime l'exercice, ou la sensation d'être en bateau sur l'eau, ou veut utiliser la voie des eaux pour se rendre où il désire, et celui qui s'entraîne pour une course; la différence entre taper du pied dans un ballon et jouer un match de football; * la différence entre monter à cheval près de chez soi ou monter à courre. Assurément, ni le sportif ni l'alpiniste ne peuvent être accusés de rechercher simplement leur plaisir. Tous deux sont artistes; et le fait qu'il ait en vue une expérience émotionnelle ne distingue pas l'alpiniste, pas même du passionné de football Mais il y a l'art et l'Art. Il est possible de faire une distinction entre les artistes. Sans classification exacte ni ordre de mérite, nous faisons habituellement cette différence : •les « beaux-arts » sont probablement qualifiés ainsi parce que nous considérons que tous les arts ne sont pas beaux. L'épithète artistique est généralement réservée à ceux dont le sens artistique est considéré comme développé à un degré particulier. C'est précisément en faisant ces distinctions que nous pouvons préciser ce que nous cherchons à déterminer: la valeur de l'alpinisme dans l'ensemble de notre expérience émotionnelle. A quelle partie du sens artistique de l'homme appartient l'alpinisme? A la partie qui lui permet d'être ému par la musique ou la peinture, ou à la partie qui lui fait apprécier un jeu ? En posant ainsi la question, on perçoit d'emblée l'abîme qui sépare l'arrogant montagnard du sportif. Il semblait tout à fait naturel de comparer une journée dans les Alpes à une symphonie. Pour les alpinistes de mon genre, l'alpinisme s'y prête à juste titre; mais aucun sportif ne pourrait ou ne voudrait prétendre à cela pour le cricket, la chasse, ou son sport, quel qu'il soit. Il reconnaît l'existence du sublime dans le grand Art, et sait, même s'il ne peut pas le ressentir, que sa manière de toucher au cœur est tout autre et plus vaste. Les alpinistes, eux, n'admettent aucune différence sur le plan émotionnel entre l’alpinisme et l'Art. Ils prétendent que quelque chose de sublime est l'essence même de l'alpinisme. Ils peuvent comparer l'appel des cimes à une mélodie merveilleuse, et la comparaison n'est pas ridicule.

George Leigh Mallory. (1914). The Mountaineer as Artist. The Climbers Club Journal, (No 3), 28-40. https://climbers-club.co.uk/history/journals, https://ccjournals.ams3.digitaloceanspaces.com/1914%20No%203_web.pdf