À la fin des années 1960, dans un contexte de turbulences politiques, de remises en cause radicales de l’ordre social et de quête de nouvelles formes de vie, Doug Robinson publie deux textes devenus emblématiques dans l’histoire de l’escalade. Pourtant, leur force ne réside pas seulement dans les contenus qu’ils exposent, mais dans la manière dont ils déplacent discrètement les régimes de valeurs associés à la pratique. The Climber as Visionary (1969) et The Whole Natural Art of Protection (1972) agissent comme des perturbateurs doux dans le champ de l’alpinisme occidental : ils réécrivent les fondements mêmes du rapport à la verticalité, à l’équipement, au geste, au monde.

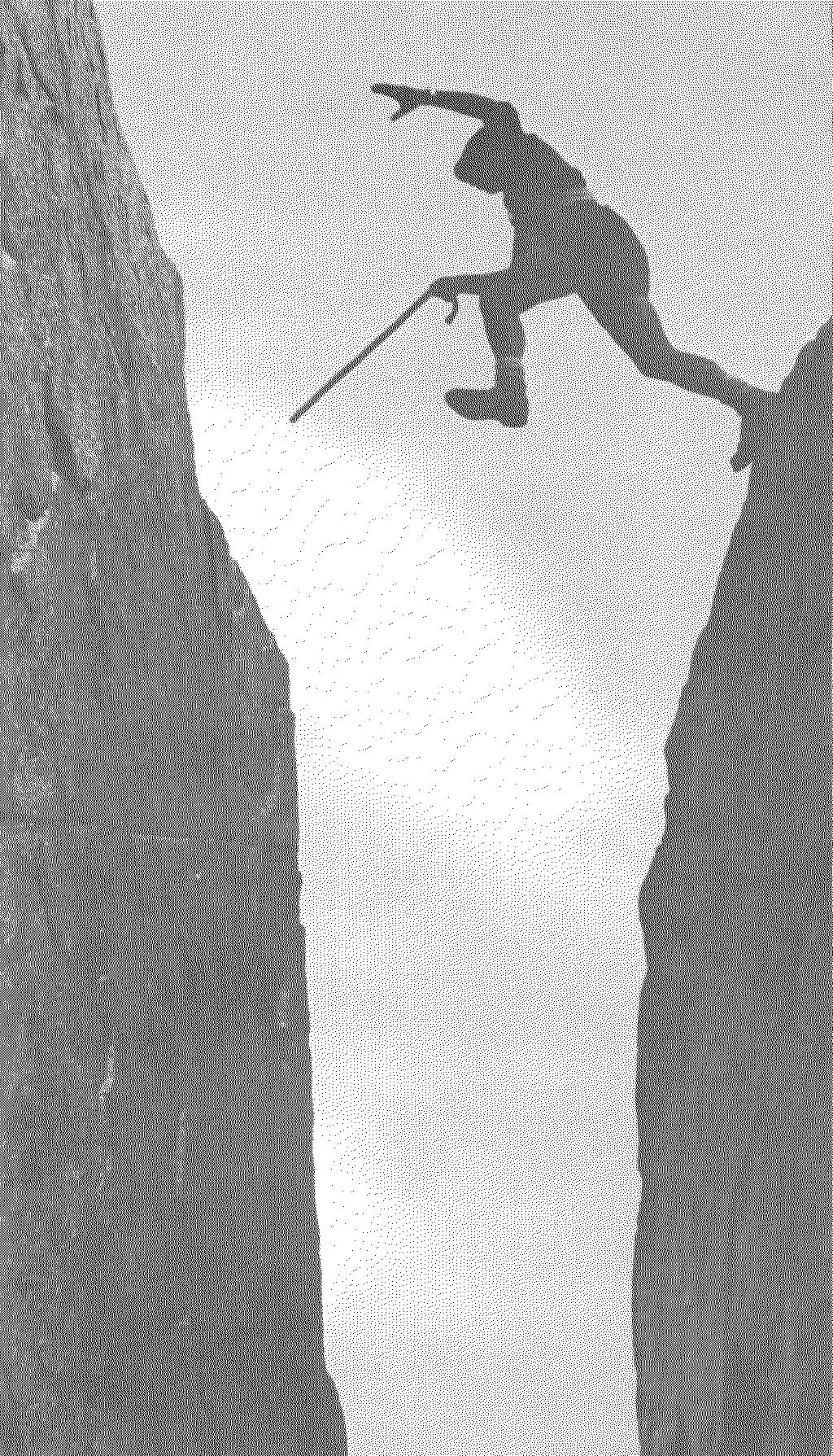

Dans The Climber as Visionary, Robinson esquisse une figure du grimpeur profondément étrangère aux récits héroïques de l’alpinisme traditionnel. Il ne s’agit plus de vaincre la montagne, ni de démontrer une supériorité technique ou physique, mais d’ouvrir un espace perceptif, un état de conscience modifié où le rocher devient terrain de relation plutôt que de performance. Le grimpeur est envisagé comme un médium - non pas un athlète, mais un praticien de l’attention, du vide, du silence. Ce n’est pas une vision romantique ou mystique au sens classique, mais une esthétique de la présence à ce qui résiste : matière, gravité, souffle.

The Whole Natural Art of Protection, publié trois ans plus tard, constitue le prolongement pratique de cette posture. Robinson y défend le clean climbing : une technique d’assurage fondée sur des protections amovibles qui ne laissent pas de trace. Ce choix, en apparence technique, prend chez lui une signification bien plus large. Il s’agit d’un geste de retrait volontaire : ne pas altérer, ne pas forcer, ne pas consommer le rocher. Ce minimalisme technique devient un acte politique, quasi éthique, à contre-courant de la logique extractive dominante.

Ce double mouvement – esthétisation du rapport au monde et critique implicite des formes de domination matérielle – place Robinson à la croisée de plusieurs régimes de sens. Ses textes résonnent avec les préoccupations écologistes émergentes de l’époque, sans jamais les énoncer directement. L’environnement n’est pas un objet de préservation extérieure, mais un partenaire de négociation, une présence active avec laquelle il faut apprendre à composer. Ce que Robinson propose, en filigrane, c’est une désescalade des ambitions humaines, un désapprentissage de la verticalité conquérante.

On pourrait lire ses écrits comme une tentative de reconfiguration de l’alpinisme depuis ses marges : marges géographiques (la Californie des années 60, éloignée des grandes institutions alpines européennes), marges culturelles (influencées par la contre-culture, les philosophies orientales, l’escalade nue, le yoga), marges techniques (préférence pour la simplicité, le local, le temporaire). Mais ces marges deviennent chez lui des points d’appui : c’est précisément là que peut s’inventer un autre rapport au monde – ni naïf, ni dominateur, mais attentif, précis, situé.

Aujourd’hui, les textes de Robinson conservent une puissance critique intacte. Ils s’offrent à la lecture comme des artefacts d’un moment culturel, mais aussi comme des ressources pour penser les formes d’engagement contemporain. Dans un monde saturé de récits héroïques, de dispositifs sécuritaires, de quantification des performances, ils rappellent la possibilité d’une pratique subtile, lente, articulée à une éthique de la relation plus qu’à un programme de conquête. Robinson ne propose pas une méthode, mais une posture - celle du grimpeur qui voit, non pas plus loin, mais autrement :

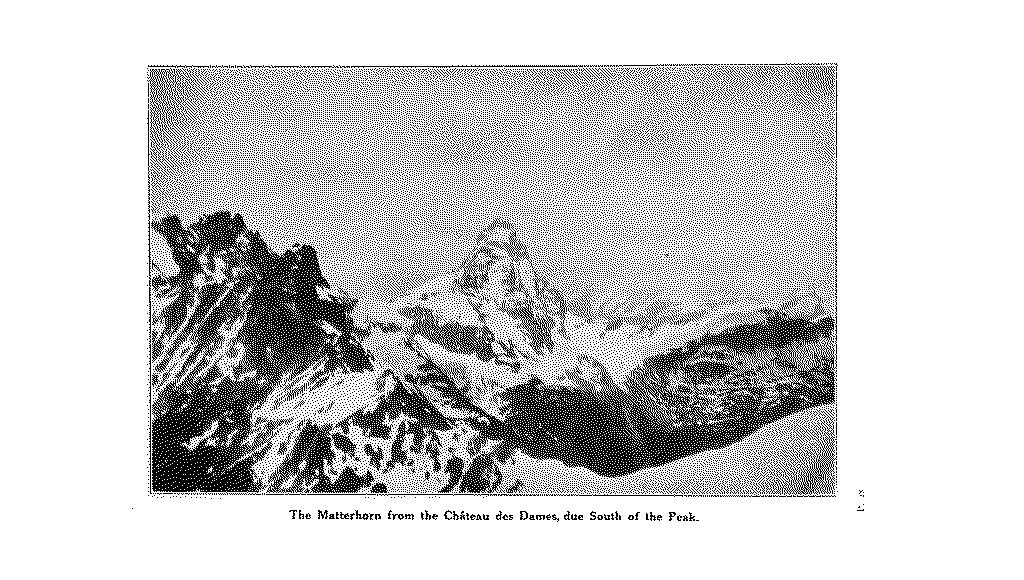

In 1914 George Mallory, later to become famous for an offhand definition of why people climb, wrote an article entitled 'The Mountaineer as Artist', which appeared in the Climber's Club Journal. In an attempt to justify his climber's feeling of superiority over other sportsmen, he asserts that the climber is an artist. He says that "a day well spent in the Alps is like some great symphony," and justifies the lack of any tangible production - for artists are generally expected to produce works of art which others may see - by saying that "artists, in this sense, are not distinguished by the power of expressing emotion, but the power of feeling that emotional experience out of which Art is made... mountaineers are all artistic... because they cultivate emotional experience for its own sake." While fully justifying the elevated regard we have for climbing as an activity, Mallory's assertion leaves no room for distinguishing the creator of a route from an admirer of it. Mountaineering can produce tangible artistic results which are then on public view. A route is an artistic statement on the side of a mountain, accessible to the view and thus the admiration or criticism of other climbers. Just as the line of a route determines its aesthetics, the manner in which it was climbed constitutes its style. A climb has the qualities of a work of art and its creator is responsible for its direction and style just as an artist is. We recognize those climbers who are especially gifted at creating forceful and aesthetic lines, and respect them for their gift.

But just as Mallory did not go far enough in ascribing artistic functions to the act of creating outstanding new climbs, so I think he uses the word 'artist' too broadly when he means it to include an aesthetic response as well as an aesthetic creation. For this response, which is essentially passive and receptive rather than aggressive and creative, I would use the word visionary. Not visionary in the usual sense of idle and unrealizable dreaming, of building castles in the air, but rather in seeing the objects and actions of ordinary experience with greater intensity, penetrating them further, seeing their marvels and mysteries, their forms, moods, and motions. Being a visionary in this sense involves nothing supernatural or otherworldly; it amounts to bringing fresh vision to the familiar things of the world. I use the word visionary very simply, taking its origins from 'vision', to mean seeing, always to great degrees of intensity, but never beyond the boundaries of the real and physically present. To take a familiar example, it would be hard to look at Van Gogh's Starry Night without seeing the visionary quality in the way the artist sees the world. He has not painted anything that is not in the original scene, yet others would have trouble recognizing what he has depicted, and the difference likes in the intensity of his perception, hear of the visionary experience. He is painting from a higher state of consciousness. Climbers too have their 'Starry Nights'. Consider the following, from an account by Allen Steck, of the Hummingbird Ridge climb on Mt. Logan: "I turned for a moment and was completely lost in the silent appraisal of the beautiful sensuous simplicity of windblown snow." The beauty of that moment, the form and motion of the blowing snow was such a powerful impression, was so wonderfully sufficient, that the climber was lost in it. It is said to be only a moment, yet by virtue of total absorption he is lost in it and the winds of eternity blow though it. A second example comes from the account of the seventh day's climbing on the eight- day first ascent, under trying conditions, of El Capitan's Muir Wall. Yvon Chouinard relates in the 1966 American Alpine Journal:

With the more receptive senses we now appreciated everything around us. Each individual crystal in the granite stood out in bold relief. The varied shapes of the clouds never ceased to attract our attention. For the first time we noticed tiny bugs that were all over the walls, so tiny they were barely noticeable. While belaying, I stared at one for fifteen minutes, watching him move and admiring his brilliant red color.

How could one ever be bored with so many good things to see and feel? This unity with our joyous surrounding, this ultra-penetrating perception gave us a feeling of contentment that we had not had for years.

In these passages the qualities that make up the climber's visionary experience are apparent; the overwhelming beauty of the most ordinary objects - clouds, granite, snow - of the climber's experience, a sense of the slowing down of time even to the point of disappearing, and a "feeling of contentment" an oceanic feeling of the supreme sufficiency of the present. And while delicate in substance, these feelings are strong enough to intrude forcefully in to the middle of dangerous circumstances and remain there, temporarily superseding even apprehension and drive for achievement.

Chouinard's words begin to give us an idea of the origin of these experiences as well as their character. he begins by referring to "the more receptive senses." What made their sense more receptive? It seems integrally connected wit what they were doing, and that it was their seventh day of uninterrupted concentration. Climbing tends to induce visionary experiences. We should explore which characteristics of the climbing process prepare its practitioners for these experiences.

Climbing requires intense concentration. I know of no other activity in which I can so easily lose all the hours of an afternoon without a trace. Or a regret. I have had storms creep up on me as if I have been asleep, yet I knew the whole time I was in the grip of an intense concentration, focused first on a few square feet of rock, and then on a few feet more, I have gone off across camp to boulder and returned to find the stew burned. Sometimes in the lowlands when it is hard to work I am jealous of how easily concentration coms in climbing. This concentration may be intense, but it is not the same as the intensity of the visionary periods; it is a prerequisite intensity.

But the concentration is not continuous. It is often intermittent and sporadic, sometimes cyclic and rhythmic. After facing the successive few square feet of rock for a while, the end of the rope is reached and it is time to belay. The belay time is a break in the concentration, a gap, a small chance to relax. The climber changes from an aggressive and productive stance to a passive and receptive one, from doer to observer, and in fact from artist to visionary. The climbing day goes on through the climb-belay-climb-belay cycle by a regular series of concentrations and relaxations. It is of one of these relaxations that Chouinard speaks. when limbs go to the rock and muscles contract, then the will contracts also. And and the belay stance, tied in to a scrub oak, the muscles relax and the will also, which has been concentrating on moves, expands and takes in the world again, and the world is new and bright. It is freshly created, for it really had ceased to exist. By contrast, the disadvantage of the usual low-level activity is that it cannot shut out the world, which then never ceases being familiar and is thus ignored. To climb with intense concentration is to shut out the world, which, when it reappears, will be as a fresh experience, strange and wonderful in its newness.

These belay relaxations are not total; the climb is not over, pitches lie ahead, even the crux; days more may be needed to be through. We notice that as the cycle of intense contraction takes over, and as this cycle becomes the daily routine, even consumes the daily routine, the relaxations on belay yield more frequent or intense visionary experiences. It is no accident that Chouinard's experiences occurred near the end of the climb; he had been building up to them for six days. The summit, capping off the cycling and giving a final release from the tension of contractions, should offer the climber some of his most intense moments, and a look into the literature reveals this to be so. The summit is also a release from the sensory desert of the climb; from the starkness of concentrating on configurations of rock we go to the visual richness of the summit. But there is still the descent to worry about, another contraction of will to be followed by relaxation at the climb's foot. Sitting on a log changing from klittershoes into boots, and looking over the Valley, we are suffused with oceanic feelings of clarity, distance, union, oneness. There is carryover from one climb to the next, from one day on the hot white walls to the next, however, punctuated by wine dark evenings in Camp 4. Once a pathway has been tried it becomes more familiar and is easier to follow the second time, more so on subsequent trips. The threshold has been lowered. Practice is as useful to the climber's visionary faculty as to his crack technique. It also applies outside of climbing. In John Harlin's words, although he was speaking about will and not vision, the experience can be "borrowed and projected." It will apply in the climber's life in general, in his flat, ground and lowland hours. But it is the climbing that has taught him to be a visionary. Lest we get too self-important about consciously preparing ourselves for visionary activity, however, we remember that the incredible beauty of the mountains is always at hand, always ready to nudge us into awareness.

The period of these cycles varies widely. If you sometimes cycle through lucid periods from pitch to pitch or even take days to run a complete course, it may also be virtually instantaneous, as, pulling up on a hold after a moment's hesitation and doubt, you feel at once the warmth of sun through your shirt and without pausing reach on.

Nor does the alteration of consciousness have to be large. A small change can be

profound. The gulf between looking without seeing and looking with real vision is

at times of such a low order that we may be continually shifting back and forth in

daily life. Further heightening of the visionary faculty consists of more deeply

perceiving what is already there. Vision is intense seeing. Vision is seeing what

is more deeply interfused, and following this process leads to a sense of ecology.

It is an intuitive rather than a scientific ecology; it is John Muir's kind,

starting not from generalizations for trees, rocks, air, but rather from that

tree with the goiter part way up the trunk, from the rocks as Chouinard saw them,

supremely sufficient and aloof, blazing away their perfect light, and from that

air which blew clean and hot up off the eastern desert and carries lingering

memories of snow fields on the Dana Plateau and miles of Tuolumne treetops as it

pours over the rim of the Valley on its way to the Pacific.

These visionary changes in the climber's mind have a physiological basis. The alternation of hope and fear spoken of in climbing describes an emotional state with a biochemical basis. These physiological mechanisms have been used for thousands of years by prophets and mystics, and for a few centuries by climbers. There are two complementary mechanisms operating independently: carbon dioxide level and adrenalin breakdown products, the first keyed by exertion, the second by apprehension. During the active part of the climb the body is working hard, building up its CO2 level (oxygen debt) and releasing adrenalin in anticipation of difficult or dangerous moves, so that by the time the climber moves into belay at the end of the pitch he has established an oxygen debt and a supply of now unneeded adrenalin. Oxygen debt manifests itself on the cellular level as lactic acid, a cellular poison, which may possibly be the agent that has a visionary effect on the mind. Visionary activity can be induced experimentally by administering CO2, and this phenomenon begins to explain the place of singing and long-winded chanting in the medieval Church as well as breath-control exercises of Eastern religions. Adrenalin, carried to all parts of the body through the blood stream, is an unstable compound and if unused, soon begins to break down. Some of the visionary experience; in fact, they are naturally occurring body chemicals which closely resemble the psychedelic drugs, and may help someday to shed light on the action of these mind-expanding agents. So we see that the activity of the climbing, coupled with its anxiety, produces a chemical climate in the body that is conducive to visionary experience. There is one other long-range factor that may begin to figure in Chouinard's example: diet. Either simple starvation or vitamin deficiency tends to prepare the body, apparently by weakening it, for visionary experiences. Such a vitamin deficiency will result in a decreased level of nicotinic acid, a member of the B-vitamin complex and a known anti-psychedelic agent, thus nourishing the visionary experience. Chouinard comments on the low rations at several points in his account. For a further discussion of physical pathways to the visionary state, see Aldous Huxley's two essays, 'The Doors of Perception' and 'Heaven and Hell.'

There is an interesting relationship between the climber-visionary and his

counterpart in the neighboring subculture of psychedelic drug users. These drugs

are becoming increasingly common and many young people will come to climbing from

a visionary vantage point unique in its history. These drugs have been through a

series of erroneous names, based on false models of their action: psychotomimetic

for a supposed ability to produce a model psychosis, and hallucinogen , when the

hallucination was thought to be the central reality of the experience. Their

present names means simply 'mind manifesting,' which is at least neutral. These

drugs are providing people with a window into the visionary experience. They come

away knowing that there is a place where the objects of ordinary sensations remind

them of many spontaneous or 'peak' experiences and thus confirm or place a

previous set of observations. But this is the end. There is no going back to the

heightened reality, to the supreme sufficiency of the present moment. The window

has been shut and cannot even be found without recourse to the drug.

I am not in the least prepared to say that drug users take up climbing in order to search for the window. It couldn't occur to them. Anyone unused to disciplined physical activity would have trouble imagining that it produced anything but sweat. But when the two cultures overlap, and a young climber begins to find parallels between the visionary result of his climbing discipline and his formerly drug-induced visionary life, he is on the threshold of control. There is now a clear path of discipline leading to the window. It consists of the sensory desert, intensity of concentrated effort, and rhythmical cycling of contraction and relaxation. This path is not unique to climbing, of course, but here we are thinking of the peculiar form that the elements of the path assume in climbing. I call it the Holy Slow Road because, although time consuming and painful, it is an unaided way to the visionary state; by following it the climber will find himself better prepared to appreciate the visionary in himself, and by returning gradually and with eyes open to ordinary waking consciousness he now knows where the window lies, how it is unlocked, and he carries some of the experience back with him. The Holy Slow Road assures that the climber's soul, tempered by the very experiences that have made him a visionary, has been refined so that he can handle his visionary activity while still remaining balanced and active (the result of too much visionary activity without accompanying personality growth being the dropout, an essentially unproductive stance). The climbing which has prepared him to be a visionary has also prepared the climber to handle his visions. This is not, however, a momentous change. It is still as close as seeing instead of mere looking. Experiencing a permanent change in perception may take years of discipline.

A potential pitfall is seeing the 'discipline' of the Holy Slow Road in the iron- willed tradition of the Protestant ethic, and that will not work. The climbs will provide all the necessary rigor of discipline without having to add to it. And as the visionary faculty comes closer to the surface, what is needed is not an effort of discipline but an effort of relaxation, a submission of self to the wonderful, supportive, and sufficient world.

I first began to consider these ideas in the summer of 1965 in Yosemite with Chris Fredricks. Sensing a similarity of experience, or else a similar approach to experience, we sat many nights talking together at the edge of the climbers' camp and spent some of our days testing our words in kinesthetic sunshine. Chris had become interested in Zen Buddhism, and as he told me of this Oriental religion I was amazed that I had never before heard of such a system that fit the facts of outward reality as I saw them without any pushing or straining. We never, that I remember, mentioned the visionary experience as such, yet its substance was rarely far from our reflections. We entered into one of those find parallel states of mind such that it is impossible now for me to say what thoughts came from which of us. We began to consider some aspects of climbing as Western equivalents of Eastern practices; the even movements of the belayer taking in slack, the regular footfall of walking through the woods, even the rhythmic movements of climbing on easy or familiar ground' all approach the function meditation and breath-control. Both the laborious and visionary parts of climbing seemed well suited to liberating the individual from his concept of self, the one by intimidating his aspirations, the other by showing the self to be only a small part of a subtle integrated universe. We watched the visionary surface in each other with its mixture of joy and serenity, and walking down from climbs we often felt like little children in the Garden of Eden, pointing, nodding, and laughing. We explored timeless moments and wondered at the suspension of ordinary consciousness while the visionary faculty was operating. It occurred to us that there was no remembering such times of being truly happy and at peace; all that could be said of them later was that they had been and that they had been truly fine; the usual details of memory were gone. This applies also to most of our conversations. I remember only that we talked and that we came to understand things. I believe it was in these conversations that the first seeds of the climber as visionary were planted.

William Blake has spoken of the visionary experience by saying, "If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite." Stumbling upon the cleansed doors, the climber wonders how he came into that privileged visionary position vis-a-vis the universe. He finds the answer in the activity of his climbing and the chemistry of his mind and he begins to see that he is practicing a special application of some very ancient mind-opening techniques. Chouinard's vision was no accident. It was the result of days of climbing. He was tempered by technical difficulties, pain, apprehension, dehydration, striving, the sensory desert, weariness, the gradual loss of self. It is a system. You need only copy the ingredients to commit yourself to them. They lead to the door. It is not necessary to attain to Chouinard's technical level - few can do - only to his degree of commitment. It is not essential that one climb El Capitan to be a visionary; I never have, yet I try in my climbing to push my personal limit, to do climbs that are questionable for me. Thus we all walk the feather edge - each man his own unique edge - and go on to the visionary. For all the precision with which the visionary state can be placed and described, it is still elusive. You do not one day become a visionary and ever after remain one. It is a state that one flows in and out of, gaining it through directed effort or spontaneously in gratuitous moment. Oddly, it is not consciously worked for, but come as the almost accidental product of effort in another direction and on a different plane. It is at its own whim momentary or lingering suspended in the air, suspending time in its turn, forever momentarily eternal, as, stepping out of the last rappel you turn and behold the rich green wonder of the forest.

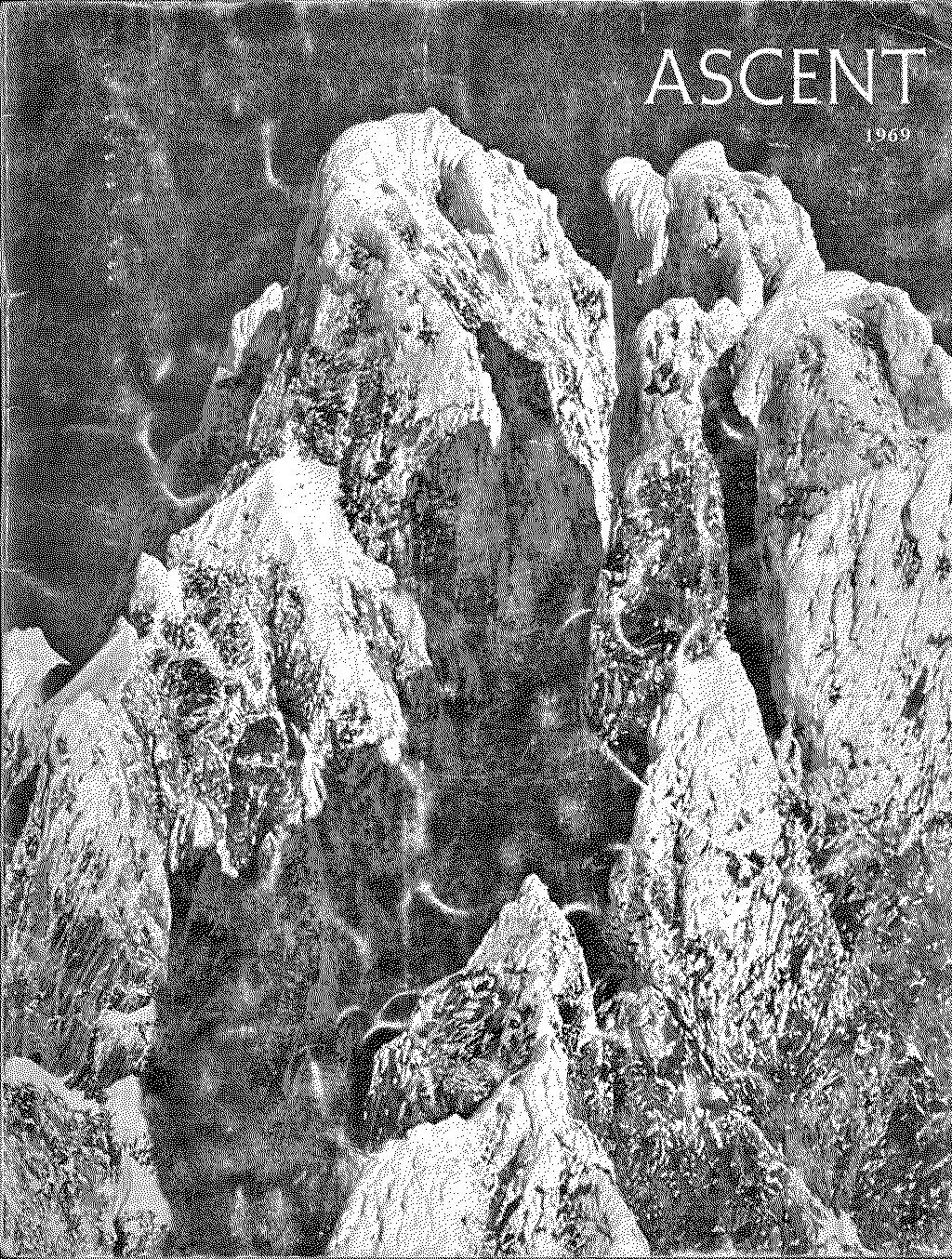

Doug Robinson. (1969). The Climber as Visionary. Ascent.

"Vedy clean, vedy clean" - Pablo Casals There is a word for it, and the word is clean. Climbing with only nuts and runners for protection is clean climbing. Clean because the rock is left unaltered by the passing climber. Clean because nothing is hammered into the rock and then hammered back out, leaving the rock scarred and the next climber's experience less natural. Clean because the climber's protection leaves little track of his ascension. Clean is climbing the rock without changing it; a step closer to organic climbing for the natural man. In Britain after thousands of ascents of the popular routes, footholds are actually becoming polished but the cracks that protect them are unscarred and clean. The "Nutcracker" in Yosemite, which was deliberately and with great satisfaction climbed clean on the first ascent, doesn't have polished holds yet, but has obviously been climbed often and irreverently; some section of crack are continuous piton scars for several feet. It can still be done with nuts - they even fit in some of the pin scars - but no one will be able to see this beautiful piece of rock the way the first ascent party did. It didn't have to happen that way. It could still be so clean that only a runner-smooth ring at the base of trees and a few bleached patches where lichen had been worn off would be the only sign that hundreds had passed by. Yet the same hundreds who have been there and hammered their marks could still have safely climbed it because nut placements were, and are frequent, logical and sound. In Yosemite pins have traditionally been removed in an effort to keep the climbs pure and as close as possible to their natural condition. The long term effects of this ethic are unfortunately destructive to cracks and delicate flake systems. This problem is not unique to Yosemite; it's being felt in all heavily used areas across the country. In the Shawangunks a popular route can be traced not by connecting the logical weaknesses, but by the line of pitons and piton holes up the cliff. As climbers, it is our responsibility to protect this part of the wilderness from human erosion, Clean climbing is a method we can use to solve this serious problem. A guide for clean climbers is here presented.

RUNNERS A length of tubular webbing or perion rope is easily tied into a loop forming one of the most versatile of natural protections - the runner. Normal single length runners can be constructed from about 6 feet of rope or webbing. Double and triple length runners require approximately 10 and 14 feet respectively. Traditionally, these loops have been tied with a Ring Bend which is simple but must be constantly watched because of the slippery tendency of nylon web and rope to untie themselves, especially when wet. A more secure knot that can be tied once for the life of the runner and can be used for both perion rope and thick tubular webbing is the Double Fisherman's Bend or Grapevine Knot (Figure 1). Runners are carried over the shoulder and under the opposite arm. In use they are looped over or around anything in sight; blocks, bulges, and bushes, chockstones and chickenheads, knobs, spikes, flakes and trees. For this reason a variety in both material and lengths of runners should be carried. All tubular webbing from 1/2"' through 1" and rope diameters from 5 or 6mm through about 8 mm are useful in fitting varying situations. The smallest sizes (1/2" and 5mm) will provide interim protection in tight threading situations. The loop strength of Chouinard 9/16" web and 7mm rope are adequate for most protection needs and 1 inch and 8mm are bombproof (see Tables E and F). A doubled runner will normally have twice the loop strength indicated. A common mistake is not having enough runners along; a dozen is not too many. Hero Loops or small runners can be used for the fine work in tying off rock spikes, nubbins, rugosities, and twigs (9/16" web is preferred for protection). Large blocks and chockstones can be tied off with a chain of runners looped together or with double or triple runners which can be carried over the shoulder in loops of two or three coils, kept even by a carabiner. Historically, runners have been commonly used in reducing the rope drag produced by out of the way protection. When climbing clean this role of smoothing out the line of the climbing rope behind the leader is even more important because the addition of a runnerwill heip protect nuts from being bounced or jerked out of the crack by the climbing rope. A runner makes a nut more secure. Sometimes runner placements themselves are insecure. For instance a placement that would easily hold the heavy downward pull of a fall might be very susceptible to a light side pull from the climbing rope. Another runner can be attached but sometimes the security can be greatly improved by wedging a pebble or nut into the crack above the runner to hold it into place. At other times extra security can be obtained by jamming the knot of the runner into place. Placements on slippery bulges might be improved by tying a slipknot in one end of the runner, then cinching it up as in Figure 2. In extra ticklish situations, British climbers have used even adhesive tape to hold runners in place on small rock spikes. Clean climbing demands vision and an awareness of the rock. On the equipment side, runners form the basis for protection. They were all that was available to clean climbing Englishmen before the advent of portable and artificial chockstones. In a like manner, they are the foundation of the modern clean climber's repertoire.

MAKE THE ROCK HAPPY - USE A NUT To plaçe a nut you must begin by thinking about the shape of cracks. Right from the start clean climbing demands increased awareness of the rock environment. Consider the taper of a crack. Is it converging, that is, flared in reverse, wider inside than at the lip? Or it may be parallel-sided with an even width. Or at the other extreme, flared. Converging cracks are easiest to fit; find a wide spot up high and drop the nut in behind. Beware of the nut falling out the bottom, however, or breaking through a thin-lipped crack. Flared cracks are easy too, usually unfittable. But important exceptions have been known, chiefly in the form of knobs or bulges in the crack which will take a nut behind or above, Also, don't overlook the possibility of fitting a much smaller nut far back in the dark recesses of the crack. The usual nut placement is in a vertical crack. Find a section of the crack that closes downward; that is, where the crack is wide above, narrower below. Select the right size nut, place it into the wide section of the crack, and carefully locate it where the crack narrows. Then give the sling a stout downward jerk to wedge the nut securely in place, Inspect the placement for adequate constriction of the crack and test the nut's security (the degree to which it can resist being accidentally dislodged by the climbing rope) by giving an appropriately light outward jerk on the sling. Nuts have the advantage over pitons in that they are more naturally at home in vertical placements. This is their normal environment as it is for the chockstones from which they derive. But the crack may not have any obvious wide-to-narrow placements. Often the difference between sliding and setting is so subtle that it can hardly be seen and is easier felt. This is especially true in granite where cracks are quite uniform and nuts were first thought relatively useless. For these trickier fittings it is helpful to have a good selection of nuts within a given size range; a small variation can be crucial. Pick the largest nut that will just fit in the crack (for Hexentrics remember that a change of attitude will slightly change the size) and work it downward until it hopefully lodges. Test it with a jerk, but avoid testing it too vigorously which will only make it harder to remove as it inches into tighter placement. Non-granite rocks have other structures to tempt the clean climber. Limestone and sandstone often have pockets that are partly closed off on the surface - sort of inverse chickenheads - that can sometimes be fitted with a nut inserted endwise and turned to wedge. To complete the range of silent protection do not overlook the potential of using certain sizes of pitons as nuts. Two general classes are possible. (1) Bongs function very well as large chocks. When used in this manner they are normally placed pointing downward with a runner threaded either through the lower lightening holes (Figure 3) or around the entire Bong as if it were a natural chockstone. Also, because they have an end taper, bongs can be wedged lengthwise in six-inch wide cracks, (Figure 4). (2) Long horizontal pitons can oftentimes be placed in cracks without the use of a hammer and have great holding power, especially in horizontal cracks. If used this way in vertical cracks, select a locally wider section of the crack or an area where the rugosities of the crack will grip the piton near each end of the blade and prevent it from rotating or shifting downward. The employment of innovative techniques such as these can turn the occasional compromise situation into good clean climbing! Finally, a few special cases. Sometimes a crack within a crack will hold a nut when the main crack won't. Very shallow or bottoming cracks or irregularities on the surface of the rock that aren't really cracks will sometimes hold a nut. Shallow cracks can more often be fitted with nuts than with pitons because a nut doesn't necessarily have to be deep to be strong. Slots on the surtace of the rock that would take only the most extreme nest of pins and then only for aid will sometimes perfectly hold a happy nut. A nut may even fit between knobs on the surface of the rock; a three-nut nest has been seen set between two knobs that was good enough for aid. Surely more imaginative ways of using them will appear.

RACKING The success of many methods of carrying nuts will depend largely upon the length of the slings. Three length categories exist (see Table C) Nuts with long slings can be carried in the same manner as runners, over the shoulder and under the opposite arm. This is probably the best carry for extremely large nuts such as Hexentrics No. 9 and No. 10. Medium length slings can be carried around the neck, necklace fashion. This is an excellent quickdraw position, but if more than a few nuts are carried this way the slings will become tangled as well as block the view of your feet. In this country the most common method is to fix the nut with a short sling and carry them clipped onto the normal hardware loop. If a large number of nuts are being carried two cleanware loops can be worn, one on each side, since the hammer will either be little used or not carried. The British carry their chocks in a variety of ways. A common one is on the equipment loops of their climber's belt or harness. Nuts with medium and sometimes even long slings can be successfully carried in this manner because this attachment at the waist, as opposed to higher on the body, prevents their swinging out front when one leans forward. It also helps to spread the equipment out over the body and keeps it out of the way of runners and equipment carried elsewhere. This method of racking can be obtained without a complicated harness by clipping the chock slings directly onto loops of the Swami Belt or the loop of climbing rope around your waist. Nuts should be racked like pitons in an orderly manner, assorted in sizes from small to large for ready access. They can be racked one to a carabiner for quicker removal. With chocks as with pitons you will want to carry a range and proportion of sizes complementing the climb - but do not forget to allow for the 1/3 more frequently needed for security. The length and type of sling affects a nut's usage. Short slings are preferred for aid climbing. Medium and long length slings are useful for free climbing because of the greater security they provide. They also facilitate jerking the sling to set the chock securely in the crack. Chocks on short slings can be set by jerking with a bight of the climbing rope after it has been clipped in. Medium length slings on chocks that will occasionally be used for aid should be made long enough so that they can be shortened up with an overhand knot. Although rope slings are preferred because of their better handling characteristics, some webbing slings will be useful for fitting into highly constricting cracks. Wire slings are used in the smallest sized chocks to obtain strength. Chocks with wire slings have advantages in aid climbing and are easier to remove, but if they are not needed for strength reasons they should be avoided in general free climbing use because of their inherently low security.

PRACTICE The question sometimes arises of tapping a nut with the hammer to seat it in the crack. Probably a holdover from piton pounding, this practice will be found not so much harmful to the rock (which is the problem with pitons) as it is to the whole essence of clean climbing. It is a bad habit. Either you are climbing clean or you are not. As if summarizing the whole ethic of British climbing Joe Brown posed the question, "When does a chock become a peg?" This is a worthwhile guideline to remember, for clean climbing is as much a battle with temptation as it is with the mountain. The use of pitons on a clean climb is somewhat analogous to the placing of bolts on a peg route. They are both antagonistic to principle. The true object, as always, is not simply to get up things and check them off in our guidebook - - it is to challenge ourselves. You have not totally committed yourself to climbing clean if you still carry the hammer and pegs with which to rescue yourself when the going gets tough. Clean climbing requires judgment and an accurate knowledge of one's own limitations; and helps in the future development of these qualities. The best way to start climbing clean is to relearn climbing itself from the ground up. Begin once again on the easy climbs, committing yourself to clean principles, using only runners and chocks for pro-tection. As before, gradually raise your standard commensurate with the development of confidence in yourself and the new equipment. Setting up practice falling situations will help in this development. The mere abandonment of hammer and pitons on hard climbs without first building the necessary aptitude can be disastrous! In due course guidebooks will list climbs that can be protected with runners andchocks only, just as they now list those that can be climbed free. When so indicated ironmongery may be totally dispensed with; the full rewards of clean climbing will be yours. Technique is more useful than force in removing nuts. They must be maneuvered into a wider section of the crack where they can be withdrawn. The fingers or the sling on the nut can normally be used for this. Smaller sizes can sometimes be nudged out with a long thin piton, or the skinny pick of a crag hammer. Wired nuts are maneuverable by their wires. A few drops of epoxy glue, welding the wire to the nut, will allow pushing with the wire to facilitate removal. The ideal of clean climbing is to climb unencumbered by pitons and the hammer. This can safely be done in areas where chock cracks are plentiful and clean. The Sierra Nevada high country is such a place. Certain other areas will require a tool for one or more of the following uses: (1) cleaning dirt, weeds or moss from prospective nut cracks, (2) for use by the second in prying or nudging nuts from cracks, particularly nuts that have been used for aid. (3) Placing anchor pitons where for some reason, a secure, non directional anchor cannot be obtained with chocks and runners, and (4) testing fixed pitons. (It still is absolutely essential to test pitons in place with light downward blows of the hammer, because of their inherently lower stability than good center pull chocks, and because they cannot be inspected visually as can chocks.)

STRENGTH ... Seen through the eyes of a lifetime of pounding, with memories of pounding harder as the fear mounts, the notion of inserting protection with two fingers, and setting it with only a stout downward jerk, tastes of insecurity. For reassurance we need to look back to the homeland of nuts where Joe Brown says that "so many people have fallen on them and been held that they seem to be at least as safe as a normal sling on a flake or chockstone", which of course can be bombproof. He feels further that the use of nuts in England and Wales has been responsible for a decline in the number of accidents. And this in a country that uses them not occasionally or for convenience, but regularly almost universally, and by extension in many less than ideal settings. Note the following report regarding the use of a small ¼" size Clog nut in Wisconsin: "Just had to let you know that I think your wired tiny brass hex is one of the most wonderful products of modern technology extant. I took a thirty foot peel onto one and it held (with the help of an excellent belay)". It would be useless to speculate on the "normal" holding power of nuts since they depend so much on the configuration of the crack. Their ultimate strength in proper placements will depend on the break- ing strength of the rope or wire sling that attaches them to the rest of the climbing system, and this in turn depends primarily on the size of the hole in the nut. The approximate strengths of rope, wire, and webbing slings in nuts are listed in Tables A and B. The approximate strengths of runners (loops tested between two carabiners) are listed in Tables E and F. Good placements in turn depend not as might be thought on the rock, but rather on the inventiveness of the climber. ... AND SECURITY The strength and security of an anchor are not the same thing. Strength is the ability of an anchor to hold a fall. Security is its ability to stay put until the fall comes. Both should be considered in placing nuts. Security can also be obtained by doubling up nuts as explained under anchoring. left on the sling will weigh it down, helping to hold it in the crack. Extending the nut sling with a runner also helps. Of the nuts that fall or pop out of the crack behind an unhappy leader, ones on wire slings are the worst offenders, usually because the wire ends up acting as a lever magnifying rope movements to pry the nut loose. For this reason medium sized and larger nuts should be put on rope or webbing instead of wire; their flexibility prevents the lever-action blues. As a general rule nuts accepting 7 mm and larger slings are not wired. Nuts with 5 and 6 mm slings are used for protecting moves and are recommended over wired nuts for insecure placements where the latter would easily be pulled from the crack, This differentiation is not a sharp one but the sizes and strengths required for mild versus serious falls is thought to grade from the one into the other at about the 7 mm level. 1 Wired chocks should be tied off with a runner to act as a flexible connection between the still nut and the moving rope. (Figure 5). In order to retain the runner's full strength it must be clipped into the wire sling with a carabiner for if it is looped directly through the wire a serious reduction in runner strength can result as indicated in Table D. We have found that plastic covering over the wire does not appreciably increase the runner's strength. After taking all these precautions the fact will still remain that many nut placements, like the infamous psychological piton, will be neither strong nor secure. The British, of course, have already recognized this problem and have a solution. They employ as many shakey nuts as necessary (or at least as many as they can get!) to do the job. They average about 1/3 more nuts and runners on a pitch than would normally be used for protection with pitons, mindful that a few will fall out, and some that stay in probably would not hold. For example, as many as 20 nuts and threads can be, and sometimes are, fitted into the very difficult but unusually well protected 120 foot Cenotaph Corner in Llanberris Pass.

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING ANCHORED Runners around trees share with pitons the quality of being non-directional anchors; pull on them any direction and you get held. Other runners and most nuts are more particular which way they are loaded - they are directional. A leader anticipating the specific direction he might be loading it, places his natural protection with that direction well in mind. But belay anchors are not so simple, and it is with these anchors that the natural climber must make the greatest effort and analysis. A belayer might be pulled down in a fourth class fall, up in a fifth class one, away from the rock or in a sequence of directions if the leader and he are unlucky. So the belayer must have a non-directional anchor, and in the absence of a handy tree or a permanent natural chockstone, he must construct it from directional tools. Ideally he will be sitting on a ledge with a converging crack at the back of it that can be chocked for a pull up or out. In this case a downward pull on the belayer would be felt as an outward one on the nut. Another method is to place a nut in a horizontal crack well to the side of the belay position, especially to the side away from a diagonal pitch, such that no force would come straight up or down on it without pulling sideways too. Mostly the answer to a bombproof belay will be several anchors set in opposition to each other so the re- sultant will hold a pull from any direction. The simplest example would be anchoring to a single vertical crack by placing one nut in the normal position for a downward pull and another somewhere below it upside down for an upward pull. The sling of the upper nut is run through the sling of the lower then clipped to the belay so a downward force is held directly on the upper nut, while an outward or upward force will pull the nuts toward each other making the anchor more secure as it gets loaded (Figure 7). Or the slings can be clipped together with a carabiner as in Figure 6. This same principle also works in a horizontal crack for anchoring and for protection where a single nut would not hold. This technique of opposing nuts can be adapted to many situations according to one's ingenuity. A nut and runner may be opposed, or two runners, three nuts... When the only possible opposing anchor points are too widely spaced to be effectively tied together, the belayer may tie-in separately to each of them, giving him one anchor for each of the possible directions he may be pulled. The belay anchor is the foundation of the climber's whole line of defense. It must be bombproof. It must be non-directional in order to safeguard a leader fall. Today's concept of extra long ropes and full length runouts is quite recent and local, being at first an adaptation to ledgeless routes in Yosemite and the ability of pitons to anchor virtually anywhere, and spreading from there by way of fashion. It is here that the natural climber will find it advisable to make a small readjustment in thinking. It is far more important to be well anchored than to make long pitches. And it is often more efficient time-wise to stop short and throw a sling over a block than run the rope out only to lose 10 minutes constructing an anchor. The British have recognized this as a part of climbing with natural protection. On English and Welsh crags pitches of 30 to 60 feet are common. Every well protected ledge is utilized as a belay stance. And the ease and quickness of placement and removal of runners and chocks make these short pitches even more practical. The clean climber may find, especially on crag climbs and alpine routes, including moving in coils, that a shorter rope of perhaps 120 feet would overall be more useful, economical, and convenient.

RELAX YOUR MIND, RELAX YOUR MIND, YOU'VE GOT TO RELAX YOUR MIND We could easily end here, having said a great deal already, but a few further implications demand notice at least. The use of nuts which begins by trying to solve some pressing environmental problems really ends in the realm of aesthetics and style. We won't pitch the aesthetics at you, only urge it once more to your atten-tion. The most important corollary of clean climbing is boldness, a trait long recognized and respected by, you guessed it, the British climbers. Where protection is not assured by a usable crack long unprotected runouts sometimes result, and the leader of commitment must be prepared to accept the risks and alternatives which are only too well defined. Personal qualities - judgment, concentration, boldness - the ordeal by fire, take precedence, as they should, over mere hardware. Pitons have their place in American climbing: aid would be very improbable without them, and many free routes will continue to need them as well. Leaving aside for now the problem of whether and how, and where they might be fixed to save the rock, we might speculate that their use in the future may be reduced to the more difficult routes. When going where cleanliness has been established the climber may leave his pitons home and gain a dividend of lightness and free-dom; but if on new ground, or the not yet clean, he can treat this unsavory equipment as the big wall climber does bolts, and leave them at the bottom of his rucksack, considering the implications as he brings them into use. There will be room for almost clean climbs that use few pins, but fixed ones, so carrying pins will still be necessary. Using pitons on climbs like the "Nutcracker" is degrading to the climb, its originator and the climber. Robbins must have been thinking of that climb when he wrote, "Better that we raise our skill than lower the climb." Pitons have been a great equalizer in American climbing. by liberally using them it was possible to get in over ones head, and by more liberally using them, to get out again. But every climb is not for every climber; the ultimate climbs are not democratic. The fortunate climbs protect themselves by being unprotectable and remain a challenge that can be solved only by boldness and commitment backed solidly by technique. Climbs that are forced clean by the application of boldness should be similarly respected, lest a climber be guilty of destroying a line for the future's capable climbers to satisfy his impatient ego in the present - by waiting he might become one of the future capables. Waiting is also necessary; every climb has its time, which need not be today. Besides leaving alone what one cannot climb in good stvle, there are some practical corollaries of boldness in free climbing. Learning to climb down is valuable for retreating from a clean and bold place that gets too airy. And having the humility to back off rather than continue in bad style - - a thing well begun is not lost. The experience cannot be taken away. By such a system there can never again be "last great problems" but only "next great problems." Carried out, these practices would tend to lead from quantitative to qualitative standards of climbing, an assertion that the climbing experience cannot be measured by an expression of pitches per hour, that a climb cannot be reduced to maps and decimals. That the motions of climbing, the sharpness of the environment, the climber's reactions are still only themselves, and their dividends of joy personal and private. After going as far with natural protection, and criticizing bolts in their turn as well, we must finally admit to still being, after all, a manufacturer of pitons, We are proud of our pitons and continue to refine their design and construction. If technical rockclimbing in places as Yosemite were still confined to the handful of residents and a few hundred occasional climbers who bought and used our first pitons then the switch to clean climbing would be purely a matter of individual preference for the aesthetic opportunities it offered, for silent climbing, lightness, simplicity, the joys of being unobtrusive. But the increased popularity of climbing is clearly being felt in the vertical wilderness, and if we are to leave any of it in climbable form for those who follow, many changes will be necessary. Cleanliness is a good place to start.

Doug Robinson. (1972). The Whole Natural Art Of Protection. Chouinard Equipment Catalog (No 72), 12-25. https://climbaz.com/chouinard72/chouinard.html